5 First-Watches for 2024

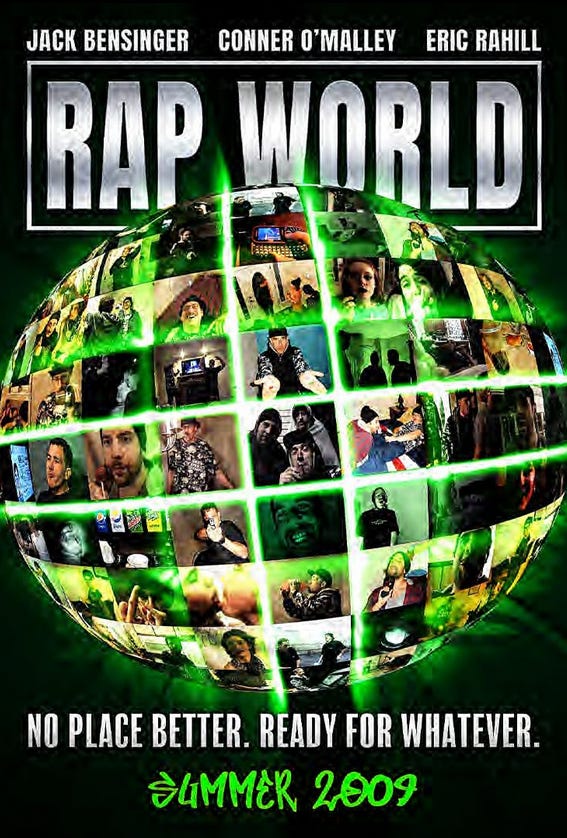

On Sambizanga (1972), Final Curtain (1957), Rap World (2024), Echoes of Silence (1965), and Back to School (1956)

Well, it’s here: the end of the year. I don’t see the value in attempting to reach for grand encapsulating statements, or even personal ones, because insofar as the divisions of the calendar are meaningful at all, this meaning only becomes apparent in much greater hindsight than this – we are still too close, too invested, we cannot yet be pitiless with ourselves (can we ever?). But, I do appreciate the excuse it gives me to write about some art I think is worth writing about, so here you go: a few words on five (5) films I saw for the first time this year (Sambizanga, Final Curtain, Rap World, Echoes of Silence, and Back to School) that I thought were very good, possibly great. These are not my “favorite” films of the year, and they are not presented in any order of preference – they are simply five that I felt I could say something worthwhile about. Four of them are old, and one of them is new – the four because I like to watch old things, the one because I do watch new things, also. Depending on the response this gets I might write more in this vein – about some albums I liked this year, say, or some books, or some more new or old movies – so if that’s something you’d be interested in, don’t hesitate to let me know. Anyway, I hope you all had a wonderful year, and that the next year is even better. Thank you for caring about what I do, or, at least, allowing me to believe you do. Here’s the list:

Sambizanga (Sarah Maldoror, 1972)

If you move in the same circles of film culture that I do (not a given, I recognize), you’ve probably already seen this, or at least thought to yourself “I should really watch that.” It’s enjoyed a rather substantial rediscovery in recent years, due primarily, I think, to the release of a beautiful new resolution in 2022, finally making it widely accessible in a form that does some justice to its images – but also, I think, to an increasing awareness that the anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist struggles of decades past are, unfortunately, anything but settled history. But still, it must be taken as a positive sign that a film such as this can enjoy such a revival at all; a steadily-paced, observationally-oriented narrative of the arrest, torture, and murder of an Angolan revolutionary by Portuguese colonial forces, and of his wife’s always-one-step-behind search for him, is not exactly something one will be inclined to throw on casually after work. Personally speaking, I had downloaded an old, discolored, hardsubbed rip of the film years before the restoration came out, fully intending to commit the necessary time, but (obviously) I never quite got around to it. I worried that it would, like so many films concerning the poor and downtrodden, ultimately be an exercise in misery, in “bearing witness” to how terrible it is that the powerful abuse the powerless – the issue being, of course, that in such a film virtue is necessarily associated with weakness, and thus the only acceptable expression of resistance is that of the martyr, who retains the “moral high ground” by refusing wipe the spit from his face, or knock the gun from his executioner’s hand. It is understandable why this is the kind of film that is normally made about the oppressed: filmmaking is an expensive endeavor, and there is much more potential return on telling bleeding-heart liberals that their empathy absolves them, rather than that it means nothing at all. But this is, of course, entirely useless to those who would like to understand why the powerful are powerful, and how that power might be taken from them.

Having previously seen Maldoror’s excellent Dessert for Constance (1981), I didn’t think it was likely Sambizanga fell into this category, but the risk is always there for a film of this description, and it’s always so dispiriting, as such films, aside from being politically useless (if not actively counterproductive), aren’t even any fun. And it is true that Sambizanga is not very fun – otherwise, however, there is no comparison. This is a film about a tragedy of struggle which understands that to engage in struggle means to accept the risk, the inevitability, of such a tragedy, and that such a risk is worth taking because the alternative is a tragedy which develops more slowly, but whose outcome is infinitely worse. It is a film inflected with the rhythms of life – real, purposeful life, life based in the conviction that to truly live, as a colonized subject, is to resist. When Domingos, the revolutionary, is dragged from his home by a gang of club-wielding comprador pigs and taken away, the women of the community are there right away, not only to comfort Maria, his wife, but to advise her, from painful experience, about what to do next. The film is full of things like this: invisible networks of wives, children, laborers, old blind men, all advising, coordinating, circulating information amongst each other and between resistance cells, operating beneath the nose of a colonial authority which, we must imagine, guesses that such networks exist, but is incapable of dismantling them. There are no illusions here, but no helplessness either: this is a film about people with agency who understand the situation they are in and understand that it will not change all at once, but only through the commitment and the discipline of a thousand tiny decisions made each day to not accept things as they are, or the role they are told has been assigned to them. Maldoror doesn’t underline this point for us because she doesn’t need to; you listen to these people and you look at what they do and this is enough to understand. And it is not fun because struggle is not fun – it is work, it is constant, conscious effort, it is stoic pragmatism; but what Sambizanga demonstrates in brilliant, vibrant color, and what the bleeding-heart narrative is incapable of recognizing (and is perhaps, in fact, ideologically invested in denying), is that just and righteous work is the most rewarding thing in the world.

Final Curtain (Edward D. Wood Jr., 1957)

I think it must be admitted that I am abnormally enamored of empty rooms. I think this is because I think of them as a kind of limit case, a space of least presence. What can happen in an empty room? Nothing. There is a sense in which they cannot really be described, as any description beyond the most absolutely cursory will eventually begin to imbue the space with presence, with habitation, simply through the force of its attention. A film, equally, can only ever really show us a simulation of an empty room, for a space which is looked upon is a space in which an event is always possible – in which, indeed, a certain kind of event is always occurring. In Final Curtain, Ed Wood demonstrates an understanding of this relation which is elemental in its clarity and stunning in its depth. Did more people share my fascination with the event of the empty room on film, as they ought to, no doubt Wood would be recognized as one of the great filmmakers of his generation, solely on the strength of what he achieves here – to say nothing of the rest of his remarkable oeuvre.

Here is what happens in Final Curtain: a man, an actor, is alone in a theater after everyone else has left. A narrator tells us he begins to believe he is not alone at all, and, eventually, he is proven correct. We can only know that the actor begins to believe this because there is a narrator who tells us this. There must be a narrator to tell us this, because the actor has no one to talk to, and there is nothing else which would give us a reason to be apprehensive, to suspect everything is not exactly as it seems. The space appears normal, because, of course, it is normal: it is simply an empty theater, a real, everyday place where Ed Wood shot for a few days, a place with stairways and catwalks, ropes and pulleys, curtains and doors. There are hard, angular shadows, of course, corners drenched in dark – but it appears as ordinary dark, benign dark. Nothing about these shadows, in themselves, suggest they are anything more than shadows (although shadows, certainly, are not nothing in themselves). But the narrator is very insistent, very animated. He speaks to us almost incessantly, and his narration is not calm and measured, is not the narration of anything ordinary; and so, slowly, steadily, surely, the shadows become more than themselves, much more, stop being ordinary, stop being benign, become filled up with lurking danger, unknowable, terrible potential. Wood does not try to increase the tension so much as refuse to diminish it, patiently cutting between shots of the actor looking, moving, searching for something he is not sure he wants to find, and shots of the space that surrounds him, which is always mundane and utterly static. These latter shots at first feel flat in the way television is flat (and Final Curtain was indeed a television pilot; it was not picked up, of course; what else could have been possible, for this great artist of failure?), and then become not flat at all, become not televisual at all, as their depth is filled out by the narrator’s words. By the end of the film, less than half an hour later, it is as though they are bottomless, which they are, because all things are, when examined closely enough. We have fallen into their depths, and are reminded we have been there before, and will return there again.