A Consideration of Some Subjects Related to Perspective and Geography

On Jobst Meyer, Anselm Kiefer, and the pathology of the Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

If you’re the sort of person that knows a lot of Americans, or likes to keep up with American culture, you might be aware that last week was “Thanksgiving” in the United States. Thanksgiving is a ritual feast holiday, derived from the raw ore of harvest festivals and religious holidays dating back, at minimum, to the Reformation, not codified into something resembling the occasion observed today until the mid-19th century. Its purpose is to serve as a mechanism by which Americans, in their seemingly bottomless narcissism, can absolve themselves of the burden of historical memory via depoliticized, antiseptic myth. It also marks the beginning of the Christmas shopping season (this is the reason it comes on the fourth Thursday in November, long after the end of New England's actual harvest season). Genocide, racism, and (actual, not mythical) colonialism are always topics on people’s minds this time of year, for obvious reasons, but these things feel especially inescapable in 2023, with our President, as of this writing, still materially supporting a genocide in Palestine whose ultimate extent, unlike that of indigenous North American tribes, is not yet simply a matter of the historical record, but an ongoing, undecided question.

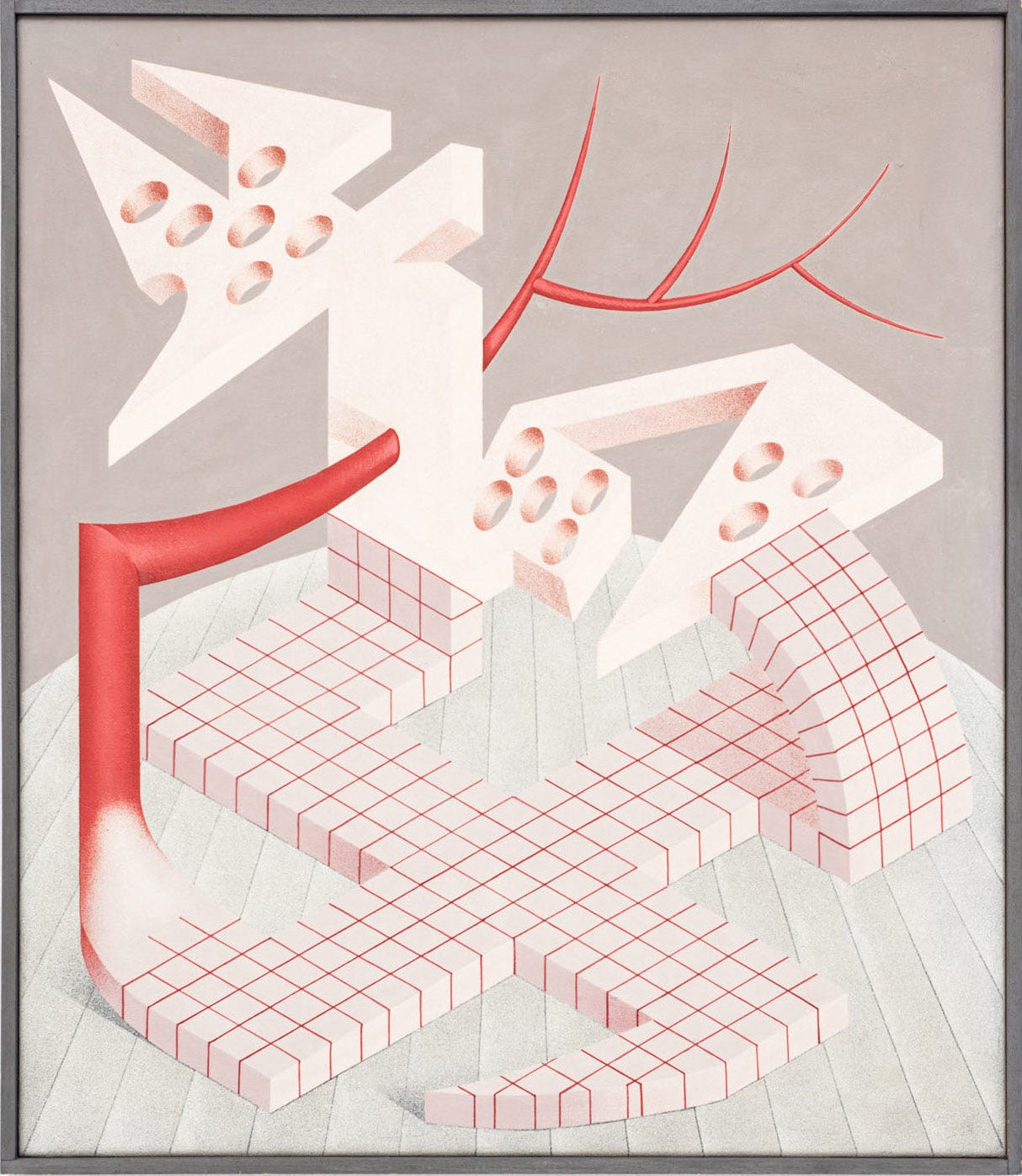

I don’t really want to talk about Thanksgiving. I bring it up only to help establish the mood of the moment in which I’m writing, on the off-chance my words should in some way outlast it. I do want to talk about Israel and Palestine – or, more accurately, I feel that I can’t not talk about Israel and Palestine, in the same way one couldn’t not talk about America and Vietnam in 1968 – but really, I want to talk about Germany, both in itself and in relation to Israel and Palestine. Really, what I want to talk about is this one painting by Jobst Meyer, called Konstruktion auf Swastika.

Meyer, who died in 2017, was an East German painter, reasonably successful but certainly not famous, a teacher for many years at the Braunschweig University of Art. I came across his work entirely by chance, clicking through old exhibition documentation as I habitually do sometimes. The first important thing to understand about him is his practice is a political one in the very oldest sense – that is, in the sense that it attempts to tell us something about the social relations which produced it. The exhibition text connects Konstruktion auf Swastika and his other work of the period with the Dutch still life tradition, and this comparison holds water not only because of obvious compositional similarities, but because Dutch still life painting, as much as it was about light, and color, and form, was always, first and foremost, about political economy. In the Netherlands, in the 16th century, a bowl of grapes, when painted, isn’t just a bowl of grapes – it’s a social position, a religion, a profession, a family history. Like is found in virtually all pre-Modernist painting, it’s a method of encoding information, and only those with the requisite knowledge will be able to read it accurately. It does not exist in a vacuum, or in a realm of pure Forms. Today, thanks to Cézanne among others, it’s possible, with great effort, to paint a bowl of grapes and have it be a representation only of itself, wholly and completely, but the same is not yet true of all things. It is these things, still indelibly stained with signification, which Meyer took as his subjects. He was a painter of strange, precise scenes existing somewhere between representation and abstraction, rendered in a smooth, polished style clearly influenced by the clean, flat, anonymous perfection of commercial illustration. One could, in fact, make the case that his compositions do exist in something like a space of pure Forms – but one seen from somewhere else. In the ‘70s, he made large paintings of hospital tents and large drawings of spiky, alien monuments, always situated in the same wasteland of gray sand, always symbolically charged but enigmatic, withholding. There are never any people around in Meyer’s work (at least what I’ve seen of it), and one gets the sense there never have been; the idea that there could be… someone inside one of his inhuman hospital tents is faintly horrifying. I’m glad we’ll never be given the chance to take a look.

It would be easy, if one were of an especially boring, middlebrow disposition, to read something about “life under totalitarian Communism” into this work, or some equally tedious cliche, but it doesn’t really hold. As an East German, in the 70s, Meyers paints détourned field hospitals and abstracted public monuments – in essence, he paints the history of the 20th century up to that point: war and Modernism. It’s a desolate drama, but one in which communism is an essentially ambiguous presence; we can perhaps say he’s skeptical, but we can’t, on this basis, say he’s opposed. This becomes clearer when one considers the later work. In 1991, he’s not an East German anymore. The DDR no longer exists. What does he paint now that the Berlin Wall has fallen, the country is unified, and a new era of capitalist freedom is dawning? What does he paint now that he’s just a German again, like he was when he was born, in 1940? He paints a symbol from his childhood, from the unity of the past: he paints a swastika. He does not, in other words, absolve himself of the burden of historical memory.

Konstruktion auf Swastika shares a basic similarity with the Meyer’s other work of this period, but it feels more unambiguous than any of them. The swastika is distorted enough by perspective and mutation that you don’t necessarily register it at first, but so aggressively patterned it’s impossible to ignore once you do. The spiraling arms bend in, foreshorten themselves, lift upwards, inwards, cut back across themselves. The structure doesn’t quite make sense, like an Escher drawing, but there isn’t exactly anything impossible about it either – it just looks wrong, like there’s been some mistake. But it’s a carefully rendered image, of course. This is what all of Meyer’s work is like – careful, deliberate, slightly impossible. The whole thing feels absurd but also, even discounting the particular implications of the swastika, faintly threatening, like a magic trick performed a bit too well, and too easily. What to make of the long, leafless tree branch rising from the lower left tine, red as a skinless arm? And what about the lower right, which resembles, vaguely, both a wilting, flaccid member and the upraised blade of a knife? There is something sad about these things, something ridiculous… but not toothless.

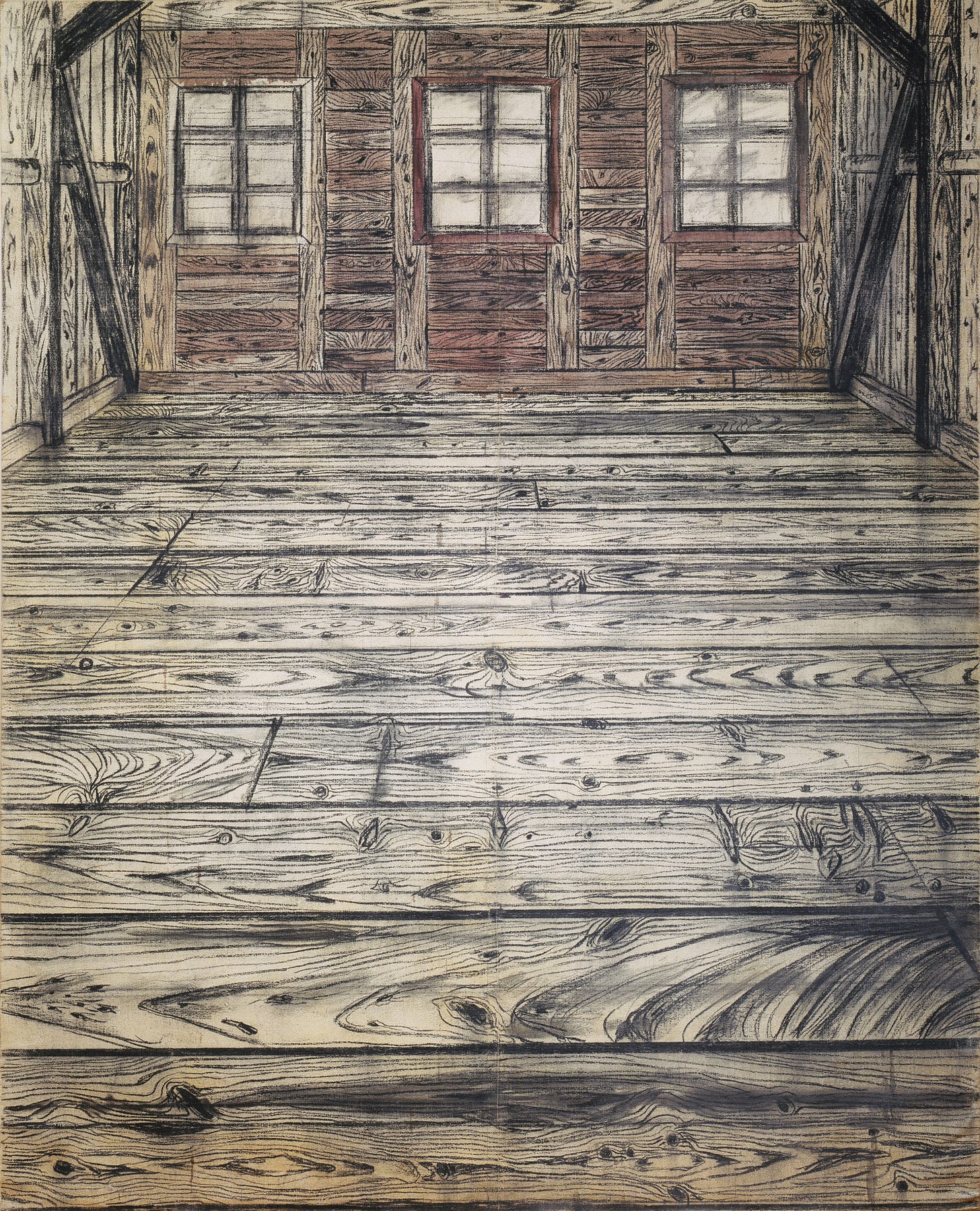

I think Anselm Kiefer is a useful point of comparison for what Meyer is doing here – not because he’s a bad painter (he isn’t), but because his prominence, and Meyer’s obscurity, tells us something both artists’ work suggests, but cannot confirm in itself. Kiefer, like Meyer, is a political artist, maybe the most successful German political artist of the postwar era (if you are willing to accept, for the sake of argument, that Gerhard Richter’s practice constitutes an engagement with something more serious than mere “politics”). But Kiefer is from West Germany, not East. He was born in a town in the Black Forest, he studied with Joseph Beuys, he lived (and still lives) in a society which paid lip service to the importance of “denazification”, but showed very little interest in actually doing it. You can see this in his work, which is monumental, nightmarish, and very marketable. It is the work of a man preoccupied with the weight of his nation’s past, not just Nazism but everything that prefigured it as well, every strangled cry and murdered dream, every Teutonic myth and Wagnerian fantasy that made possible the rubble of Blitzkrieg and the desolation of the gas chambers. The canvases, generally speaking, are huge, dark, heavy with pigment, often other materials, ash, straw, paper, lead, all splattered, defiled, scribbled upon, wretched and monstrous, strangely alchemical; they are enormously imposing, merciless compositions – viewing a Kiefer, one gets the sense, no matter what the ostensible subject happens to be, of atrocity just beneath the surface. Which, in West Germany, it kind of always was (and still is).

Kiefer, obviously, is not someone trying to absolve himself of anything – quite the opposite, he takes the burden of History, with a capital H, upon himself with an obsessive, masochistic enthusiasm. He wants you to see how heavy it all is, all the horror, all the death, all the violence. But there is something suspect in this, something dishonest. His work is like a confession which lingers too long over the details of the crime, until you have to wonder if the confessor isn’t getting something unsavory out of describing the experience. It is significant that Kiefer favors the imposing, the monumental in his work – these are forms which are inescapable, which by their scale alone force themselves upon the viewer. At root there is a sadism in them, a veiled threat, a fetishistic pleasure in the discomfort and unease they inspire in the gentle museum-goer. The work presents itself as self-loathing, as masochistic, as a condemnation, but no one makes such a grand display of their shameful past unless, somewhere deep down, they aren’t a little bit proud of it, too. Mephistopheles whispers in your ear: “You see? These Germans are a scary bunch – they’ve done a lot of evil things in their time, and I wouldn’t be so sure they’ve learned their lesson yet… better not get on their bad side!” Such is the pathology inculcated by West Germany. That Kiefer’s work sells so well (quote from Wikipedia: ”In 2017, Kiefer was ranked one of the richest 1,001 individuals and families in Germany by the monthly business publication Manager Magazin.”) is evidence he’s far from the only one attracted to this idea – and that among the likeminded are many who are very wealthy, and very powerful. Many of them outside of Germany, to be sure. But many within, as well.

Two months ago, if you asked me what my take on Kiefer was, I don’t think it would’ve been massively different from the above, but I would’ve admitted it was a bit of a stretch – at least in its broader social implications. Now, these implications seem all but undeniable. Palestine has brought that buried sadism right to the surface, made the implicit threat explicit. Having eaten the sin of the Holocaust on behalf of the entire wretched continent, Germany is now trying to vomit it back up, half-digested, onto the Palestinians, while it thinks it has the chance. What else are we to call it when their immigration authorities start trying to deport Palestinian activists over “security concerns”? When the police are called in to break up vigils for the Palestinian dead? When talks and awards ceremonies are cancelled because the speakers or the recipients have expressed solidarity with Palestine, or even simply because they happen to be Palestinian? When so-called “anti-fascists” take to the streets to shout slogans like “fight for Zionism!”, even as the Zionists bomb schools, hospitals, churches, mosques, drop white phosphorus on apartment buildings, slaughter children by the thousands, speak openly of their desire to cleanse Gaza of the “human animals” which inhabit it? Germany wants to prove it’s still a strong nation, strong like it was when the Nazis almost brought the world to its knees. But the Nazis, it’s quite sure, are gone, used up, a scary story to tell children – all that is behind them. When it sics its pigs on all the Jews and communists and assorted ethnic minorities who just can’t seem to get with the program, who, for some reason, refuse to follow the new, enlightened German party line, it does so in the name of combating hate. Having perpetrated the Holocaust, it will tell you, gives it a unique authority regarding antisemitism. It understands it better than you or I. And it is deeply antisemitic, it will tell you, to question Israel’s right to kill thousands of people in the ghetto it has trapped them in. It gives Germany a strange pleasure to tell you this, a pleasure which, for it, remains carefully unexamined.

Meyer, I think, understood this little dance Germany does very clearly. It’s abnormally explicit in Konstruktion auf Swastika, but it’s there in the more semiotically abstract paintings, as well. Kiefer probably understands it, too, to some extent, but there is an aspect to it which Meyer’s work reveals and which Kiefer’s hopelessly obscures – namely, just how pathetic it all is. Konstruktion auf Swastika is not a particularly large painting. It’s not tiny, but unlike Kiefer’s canvases, it’s human-scaled. It can’t force itself on you. The hard lines, sharp points, bizarre geometry – it’s all a little threatening, but the threat is empty. We can hold it at arms length, like a squirming mouse, and look at how it flashes its teeth and pedals in the air. Meyer’s painting shows us the roots are still there, the history, the real death, the real hatred, the real desire for fascism – none of it’s gone away; but in the cold light of the post-Soviet day, it’s all become a little ridiculous, like the rape fantasies of an impotent bureaucrat. Germany isn’t an empire anymore, hasn’t been for a long time. Meyer’s swastika, all bent and distorted and fucked up, would make a poor emblem upon a banner. It’s simply an administrator of the liberal world order now, a cog in a machine it does not control – a machine no one really controls. Thus it has to get its kicks by proxy. There will not be a new Hitler because it’s no longer a nation interested in producing Hitlers, only endlessly competent, interchangeable officials who will sometimes, for reasons even they might not fully understand, make it a personal priority to support some other Hitler-esque in some other nation, very far away, too distant for them to ever have to worry about the smell of rotting corpses wafting in through their office window on a balmy September day. Meyer understood that after tragedy, of course, comes farce. Kiefer, and those like him, are under the impression that it’s just tragedy all the way down, and they take a certain pride in it. East Germany, West Germany. Konstruktion auf Swastika is a painting about the future of Germany, the future that’s happening now. The future it depicts is a very mean joke.