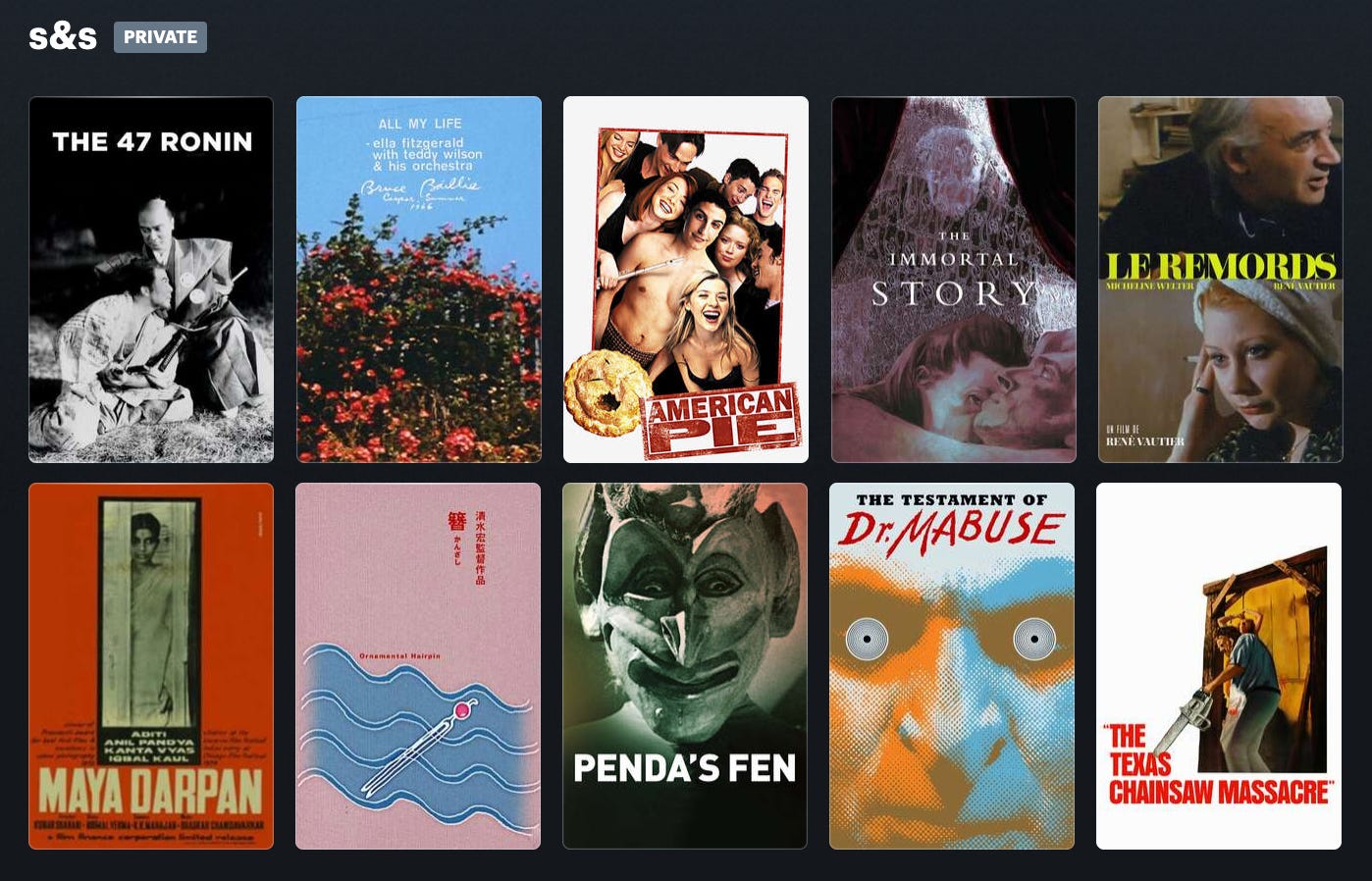

A List of Ten Movies

Some self-indulgent notes on an exercise in self-indulgence.

First in 1952, and again every 10 years since then, a magazine you might have heard of called Sight & Sound has asked a select group of directors and critics they deem important to send them a list of the ten films they believe are the Greatest of All Time, then tallied and published the results as a ranked list of 100 films. This list is, at present, the closest thing to an authoritative “canon” we have in the film world, and its latest iteration will be published tomorrow, December 1st. Of course, it’s always functioned more as a barometer of the cultural mood rather than anything actually determinate, and as the number of ballots increases with every iteration, with their relative weight decreases in kind, it becomes more and more difficult to say to what extent it even does this. But one thing that can be said with certainty is that it provides an excuse for the two things movie people love doing more than anything else: making lists and arguing about lists. I’m far from an exception to this, so naturally I put together a speculative ballot of my own, and because I think very highly of my own taste I wanted to expand on my choices a bit here, sort of walk you through my thought process and what each film means to me. The arguing will have to wait until the official list drops. Now, here’s what I went with:

Some of these selections would probably be different a month from now. Some of them definitely wouldn’t be. I made a conscious effort to limit the number of Amerikan movies on the list, which meant painful decisions like “no John Ford”, but otherwise I tried not to be too neurotic about it (thus no silent films, no animated ones, etc.). The order is, of course, alphabetical.

The 47 Ronin (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1941) — This is definitely the odd one out on the list. It’s the only one I have logged at 4 stars (every other is 4½ minimum), and I’ll freely admit it’s not even my favorite Mizoguchi (that would be The Crucified Lovers or possibly Sansho the Bailiff, which I need to rewatch), but it fills two very important niches: 1) at 4 hours it is a Very Long Movie, and 2) as a film mostly consisting of long, static shots of samurais having conversations about the particularities of their code of ethics, it is a Very Boring Movie. It is essential to have both of these niches filled if you want you spec ballot to appear “serious”. Using the same film to do both actually grants bonus points, as it shows you’re really serious about being “serious”. The 47 Ronin isn’t actually boring, of course, it is gripping in a way few films have ever been, but it is Boring in the sense that it believes what it is doing is worthwhile in itself, and does not need to be justified. In a sense this is a stand in for the painfully omitted Straub-Huillet, as like most of their work it is an adaptation of a classic text which devotes itself to the task of making it appear on the screen with the greatest clarity possible, such that its political and dramatic stakes, and their interrelationship, are made unmistakably apparent, and in so doing enriches both the cinema and source text. That Mizoguchi was able to bring this sensibility to a work of wartime propaganda should make clear that he belongs in the very uppermost echelon of “political” filmmakers, if that were ever in doubt.

All My Life (Bruce Baillie, 1966) — This is the most beautiful film ever made. Not much more to it than that. Baillie, overall, is a filmmaker I respect more than love, but one day in 1966 the light of the Divine must have come down and touched him, so that he might share with us a glimpse of the eternal. I hope it’s the last thing I see before I die.

American Pie (Paul Weitz / Chris Weitz, 1999) — On the opposite end of the spectrum, now, from the miraculous and eternal is a film of the cheap pleasures, of laughter, of sex, of youth, and which on these terms is no less perfect. In a genre and an era which so frequently got its kicks from pointless cruelty and sadism, here is a film in which every character is ultimately revealed to be as worthy of respect as any other – not in the service of hackneyed pathos, but simply because it’s funnier that way. There are several teen comedies I admire, and a few I really love, but none as much as this, a perfect diamond drenched in cum. This is the main reason it’s on this list, but it also serves to fill another niche on the “serious” spec ballot, no less important than the Very Long Movie or the Very Boring Movie: the Very Popular Movie, whose presence is necessary to signify that you pay no mind to the so-called “High-Low Divide”, and, as a truly discerning viewer, are capable of recognizing exemplary works regardless of their critical pedigree (American Pie is actually rated fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, but these sort of things are to be ignored). It’s important that you actually love the movie, though. If you’re faking it everyone will be able to tell.

The Immortal Story (Orson Welles, 1968) — Welles’ most magical film, beautiful and ethereal like a flickering candle flame. This also fills an important niche: the Contrarian Auteurist Movie. Citizen Kane is all but a lock for the top 5, and there are another five Welles picks that no one would bat an eye at, but claiming The Immortal Story, a film not even an hour long and full of visible seams, as his greatest accomplishment? Now that’s a unique take. That’s a statement. But here’s the thing: it really is that good. The story of Welles’ career is one of compromised vision, and this film is no exception, but it’s the only one that doesn’t feel compromised. The seams don’t feel like seams, but elisions formed in a memory or a dream, something whose flaws are part of its perfection. It is one of the greatest of all films about storytelling, because it understands that a truly great story is woven from such slender thread that, if the light were not cast on it just so, it would perhaps not be known to exist at all.

Le remords (Nicole Le Garrec / René Vautier, 1974) — Real heads will know that this is the namesake of the blog-type entity that proceeded Garden Scenery, and not for nothing: these 12 minutes are, I think, probably the most important statement on the political economy of filmmaking ever produced in any medium, a brutally hilarious deconstruction of every comfortable lie the “radical” director allows himself to believe, from the importance of the “statement” he makes, when that statement can only come after the fact of injustice, and never act directly against it, to the presumption (in 1974) that he is a man among men, and how he relates to women has no bearing on his political bonafides. Perhaps one of the only truly Maoist films, in that it is an act of ruthless self-criticism which arrives not at a place of nihilistic abnegation, but rather that one’s duty, first and foremost, is to serve the masses, and art is never an excuse to neglect this. If I could make every self-proclaimed “cinephile” watch one film, it would be this.

Maya Darpan (Kumar Shahani, 1972) — Arguably the most outright “difficult” work on this list, at least for me to talk about. An obscure, beautiful tessellation of images in and around the expansive home of a wealthy but declining industrialist, trying and failing to cling to his fortune as his daughter drifts slowly and inexorably deeper into a relationship with an engineer of a lower caste. The managing of space here is as great as anything Bresson achieved. This is Shahani’s first film, and the first of his I saw, and while his later work is also frequently great, nothing has left as strong an impression as this, which contains several moments as bright and piercing as the sun thrusting through a blanket of clouds.

Ornamental Hairpin (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1941) — Like The 47 Ronin, a Japanese film from 1941 which hinges on adherence to socially-enforced codes of behavior, but otherwise quite different. Where Mizoguchi’s film exhaustively elaborates the logical necessity of its foregone conclusion, Shimizu’s leaves all its greatest truths unspoken, ensconced in the rhythms of a long, idle summer, where nothing seems to be of any great importance until suddenly we realize it is all of the absolute greatest. If anything, the closest point of comparison is The Immortal Story, which is similarly slight in structure and weighty in effect. Mostly this film on here because it broke my heart.

Penda’s Fen (Alan Clarke, 1974) — This one changed my life.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933) — The best of Lang’s German films, and possibly his best overall, a vision of Weimar Germany as a labyrinth of claustrophobic rooms and barren streets, prowled by diabolical murderers hiding behind endless puppets, doubles, facades, and as such it is one of the very greatest films about fascism. There’s a sense of creeping doom here which rivals that of any horror film that came after it, but Lang is too clinical, too remorseless, to allow us the release of true terror. Lang is sometimes accused of being an overly cold director, but it’s not really true – it’s the world that’s cold; he just lives in it.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) — Speaking of true terror, here, finally, is the final entry on my ballot, and entirely coincidentally the very greatest of all. I’ve written fairly extensively on this film elsewhere, and there’s both too much and too little else I could say about it, as it contains such immense depths, and so much of those depths are unspeakable, inexpressible in common language. It fills the necessary and important niche of Actually Scary Horror Movie, by which you demonstrate that you’re not afraid of “ugly” or “disreputable” art (nevermind that this film, by now, has been recognized as an unambiguous masterpiece by anyone worth paying attention to), but realistically that wasn’t really a factor in my choosing it, which was as inevitable as the tides. Suffice it to repeat the things I say whenever it’s brought up: that it’s the Great American Film, and, by extension, the greatest film ever made.