Not Heaven

On Sheer Hellish Miasma and Sheer Hellish Miasma II by Kevin Drumm

Fifteen or so years ago, when I was first getting seriously interested in music, what I wanted to know about more than anything were the limit cases. With the same peculiar neuroticism that had already led me, in my pre-teen years, to develop a kind of juvenile obsession with both the dry, ironic intellectualism of ‘70s conceptual art and the visceral physicality of ‘60s Aktionism, I tried to seek out, as best I could, documents of the known limits of recorded sound – the most complex, the most simplistic, the longest, the shortest, the quietest, the loudest, and so on and so forth. I didn’t really know what I was doing, and this was a time before there existed “iceberg memes” with 2-hour long breakdown videos for every topic imaginable, so I pulled whatever leads I could from whatever sources I could in a more or less undiscerning way, in the way children tend to do. This was the waning years of the “Blogspot era,” which is to say the heyday of weird Central European guys eager to tell you in slightly clunky English that this or that muddy Industrial tape or inscrutable Serialist platter was actually a radical and groundbreaking forgotten masterpiece, and so at first I got myself lost down a lot of blind alleys, sitting through a lot of disappointing albums, but as I began to find my footing on the terrain, I began to notice that there were certain artists and certain releases which were referenced with such consistency and across so many disparate sources that the presence of a genuine point of consensus became unmistakable. On the question of “harshest album ever,” there was no one answer everyone agreed on, of course – the question, past a certain point, is entirely subjective and in any case certainly pointless. But, with that said, there was one album which seemed like it was always in the conversation, wherever I looked: Sheer Hellish Miasma, by Kevin Drumm. That album was released in 2002. Earlier this year, almost a quarter century later, Drumm released Sheer Hellish Miasma II.

SHM, as I’m going to refer to it from here on, did not have the profile of a typical harsh noise album, in 2002 or in any other year. Then, as now, the vast majority of harsh releases came out on specialty microlabels, which put out extremely limited editions in economical, often hand-assembled, intentionally-crude packaging for a marginal audience of committed enthusiasts – SHM, though, was a sleek, professional CD (not a CD-R, a CD) published by the Austrian label Mego, a leftfield electronic label with a significantly higher profile and broader customer base than even the most prominent noise labels of the day. As such, SHM functioned as something like a diplomatic emissary for harsh noise, a demonstration of its seriousness as an artform to those who might otherwise be skeptical – no poorly Xeroxed bondage art or autopsy photos on the cover, no misanthropic track titles, no shock tactics at all, really, just an austere black rectangle, with Drumm’s initials emblazoned, in lowercase, on the front; the sounds within, the implication seemed to be, could speak for themselves.

And they did, is the thing. I have never been someone who needs art to look “respectable” to take it seriously; I am not put off by shock tactics, by gore or pornography or references to historical atrocities – honestly, I find that stuff kind of charming, most of the time; I consider it part of the “experience.” I am exactly the sort of guy who would have been buying Mother Savage and RRRecords tapes by mail-order in the ‘90s, if I had been born 20 years earlier, is what I’m saying. But if you are the sort of person that’s bothered by that sort of stuff, it’s no obstacle to loving SHM, because its presentation is entirely anodyne and inoffensive, and that presentation frames what is quite simply a phenomenal harsh noise album, entirely deserving of its canonical status. It is not, for the record, the “harshest album ever” (jut for starters, there are any number of Hijokaidan or Incapacitants releases that I would argue surpass it on that front), but it is very harsh, and, more importantly, very calculated. For a form often (mis)perceived as centering raw intensity and provocation over all else, SHM is a necessary corrective, an unmistakably deliberate, controlled, composed album, with a dynamic structure and clear progression across its track listing, four pieces ranging from three minutes to almost half an hour, each distinct from but in conversation with the others, together probing at a set of aesthetic concerns which are grounded entirely within the sound field, rather than simply grafted onto it via cover art, track titles, etc. – in this sense it is very abstract, strangely distant, even refined; it is as intense, as infernal as any great harsh album but it has no aggression, it is not trying to intimidate you, it is not trying to do anything to you, it is at work on more important matters, it does not care that you exist. Harsh noise has always been about much more than just making the loudest, most obnoxious racket possible, but before SHM, one could be forgiven for believing otherwise. After SHM, there was no longer any excuse.

Of course, no one needs to be told this today. The internet has made it trivially easy for the even passingly curious to get a crash course in noise history and for the initiated to keep up with all the most exciting work being put out today. Anyone who cares to hear it already knows noise is a serious artform – and if not, well, you can go listen to SHM and find out right now. It’s certainly worth your time. My point is, noise is in a very different place now than it was in 2002. More importantly, the world is in a very different place now than it was in 2002. SHM is a special album because it was exactly what its particular historical moment called for – and now, in the very different historical moment on 2025, there is a sequel, there is Sheer Hellish Miasma II. Let’s take for granted that Drumm is not an idiot, and understands the significance of that first album, and the level of expectations it creates for any legacy sequel. On this basis, what can SHM II, by its form and its context, tell us about noise today?

There is, first, the matter of the label, Erstwhile Records. Once again, like Mego, this is a label which has released noise albums before, but which is not really a “noise label.” Erstwhile emerged in the early aughts as one of the essential labels documenting the then-exploding (relatively speaking; it should go without saying that everything I’m talking about here is happening so far beneath the cultural “surface” as to make nary a ripple) Electro-Acoustic Improvisation scene, putting out some of the most important releases by many of its most important practitioners (my own copy of the Good Morning Good Night 2xCD is one of my more treasured possessions). Since then, mirroring the trajectories of many of the artists it featured, the label has expanded its focus into ever more abstruse fields of sonic exploration, releasing dense, mysterious sound collages, realizations of ultra-minimal graphical scores, monumental compendiums of unadorned field recordings, and, it should be noted, still quite a lot of entirely improvised work. Erstwhile, a quarter-century-old enterprise at this point, has become a kind of banner-carrier for a certain philosophical attitude towards the sonic arts, a belief in the value of sound-as-sound and sound-as-environment, one whose manifestations are too diffuse and heterogenous to be captured under any single name or within any single rubric, but which is nonetheless totally distinct and recognizable. To my knowledge, they’ve never released anything which could be considered straight-ahead harsh noise before this year, but it’s certainly territory which they’ve brushed up against from time to time, such as the two collaborations between Drumm and tape wizard Jason Lescalleet, operating in a Musique concrète mode, which they released about a decade ago. With Drumm himself being now an elder statesman of not only noise music, but “experimental” music in general, when the announcement came that they would be releasing SHM II, it really just made sense. Frankly, I’m not sure what other label has the pedigree for a release like this. There’s adventurous, exciting new imprints popping up every month, certainly, but adventurous, exciting old ones, with the sort of resources a release like this deserves, are only getting rarer. Peter Rehberg, the founder of Mego, passed away several years ago.

Having considered the label, let’s now consider the most basic observable attributes of the work itself: its track lengths and its overall runtime. SHM, as previously mentioned, consists of four tracks with a total runtime of fifty-three minutes. SHM II, on the other hand, consists of only two tracks, but with a total runtime of ninety-five minutes, more than forty minutes longer. Further, while SHM takes the form of two (relatively) long tracks bookended by two (relatively) short ones, SHM II’s two tracks are both marathons, one forty-two minutes long, the other fifty-two, taking up a disc apiece of the 2xCD release. The thing to notice about this is that SHM, despite its aforementioned abstraction, is structurally narrativistic – its pacing and sequencing gives it a dramatic arc, a curve of rising and falling action, a beginning, a middle, and an end. The “story” might be one of pure sonics, but there is clearly some sort of “story” there. SHM II, on the other hand, hardly possess a structure at all. It is one step away from the most blunt of all album structures, the single long track. While I’m sympathetic to the concept that all temporally-determinate art forms (of which recorded sound is certainly an example) are intrinsically narrative, on some level, this dimension of the work is not meaningfully evident within SHM II’s structural schema. To the extent that it is present, it is present within the tracks themselves.

So, yes. What about the tracks themselves? Well, I can say I think they’re among the finest works of harsh noise ever recorded, but of course, that isn’t very meaningful or illuminating observation, in itself. This is where the would-be critic tends to retreat into either a self-reflexive meta-commentary on the difficulty of writing about an artform as abstract as noise music, or the florid, empty verbosity of “music writer prose” (you know what I’m talking about), but I believe in doing things the hard way, so instead I’ll make a concrete observation, and try to develop a substantive line of argument from it: these tracks are far more “wall”-based than the compositions on SHM, and I think this is significant. The way I remember it, it used to be the case, at least for a certain type of younger, more self-conscious noise enthusiast, that wall noise (meaning, noise which is especially static and unchanging in nature, which eschews dynamic variation and generally all those techniques of composition through which noise might otherwise assert a connection, however tenuous, to what is generally understood as “music”) was the Bad Object which embodied all the negative stereotypes of noise as lazy and juvenile and “just static”, and against which SHM, in particular, was often held up as argument-ending counterexample, a record which proved that noise was as serious and legitimate and “artistic” as any other genre. There are obvious parallels to this attitude across many historical periods and many forms of music, popular or otherwise; I’m sure you can think of some on your own. The point here is that for its sequel, then, to be two tracks of crushing, uncompromising, full-blast wall suggests not only a repudiation of the insecurity this discourse represented, but also the development of a totally distinct line of thought about what it means to do noise “seriously.” The direction Drumm seems to be pointing here is not towards the reconciliation of noise with conventional musicality, as SHM in some ways suggested, but rather outwards into the great, vast regions beyond that sheltered little enclave, the place noise came from and the place it will return to – not noise-as-music, but noise-as-sound.

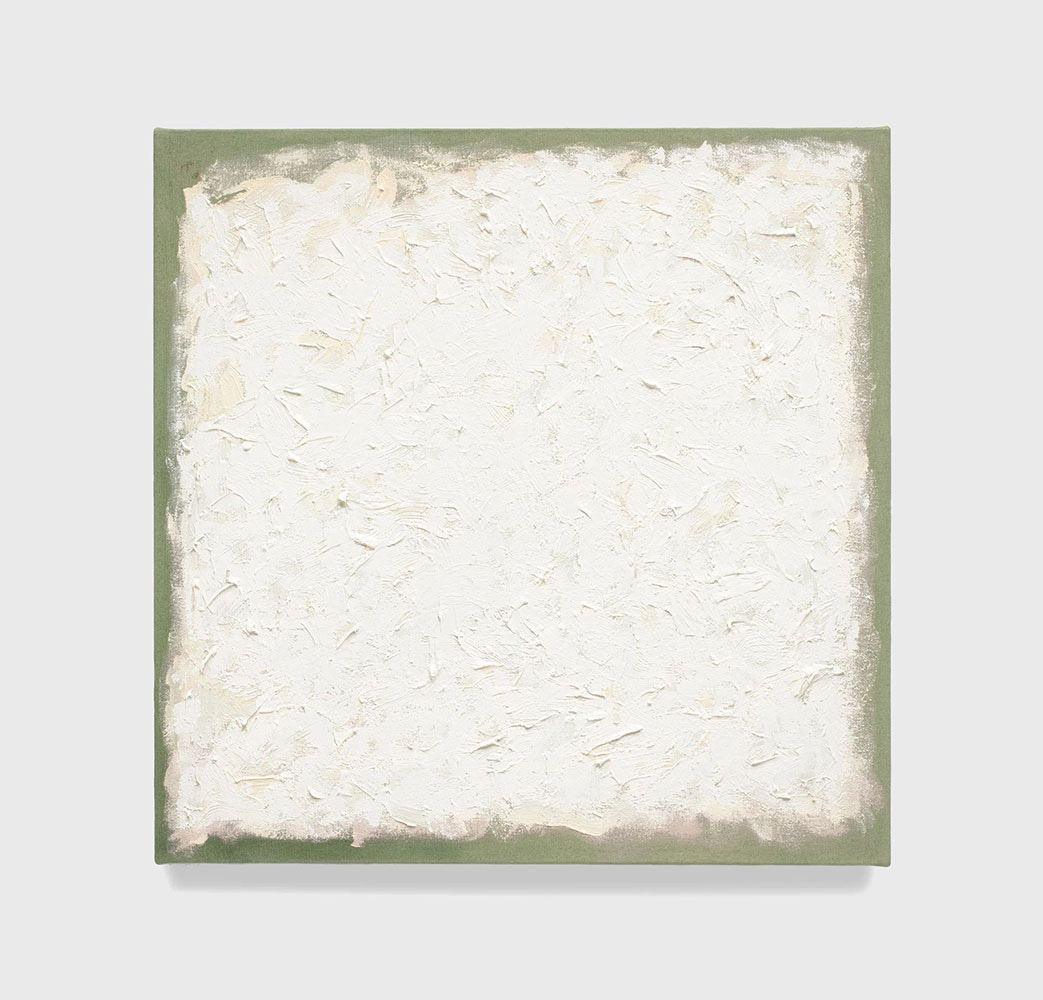

To be sure, the walls of SHM II are not the totally featureless monoliths of genre purists like Vomir – both tracks here, “Exorcism” and “Icepick,” are incredibly rich, deep and, most importantly, distinctive soundscapes, built up out of innumerable layers of constantly shifting tone and texture. I don’t really think there’s anything wrong with making a wall by simply setting your gear up and letting it blast for a while, in the same way I don’t really think there’s anything wrong with covering a canvas in a monochrome wash and calling it done, but it is overwhelmingly obvious that this is not anything like what Drumm has done here, that these walls are as meticulously composed as anything on this album’s predecessor. “Exorcism” might sound totally flat and chaotic at first, but if you actually pay attention, you’ll realize that, in addition to the aforementioned many layers of shifting tone and texture, it actually has several distinct phases with clear transition points, and “Icepick” even has something resembling an intro, over a minute of relatively muted swarming insectoid noises before a bassy drone kicks in and the full weight of the piece manifests itself, as well as an outro of similar character. To extend the painting metaphor, what work like this reminds me of, in terms of its compositional logic if not its affect, is not Nitsch, say, or Malevich, or any of the Color Field painters, but Robert Ryman, who spent half a century painting almost exclusively with white pigment, not as some sort of conceptual provocation or stylistic shortcut, but as a means of probing at painting’s most fundamental properties, the materiality of pigment applied to surface, stripped of as much of the philosophical and conceptual baggage “pigment applied to surface” as accrued over the centuries as possible. Ryman’s paintings are not dry, repetitive, or impersonal: they are absorbing, singular, intensely tactile, intensely present, intensely involved with the world, visibly works of craft, of human hands acting on something in the world. They constitute a method of inquiry which is both systematic and intuitive, rigorous and open, disciplined and free, a form and a practice continually pushing forward and doubling back on itself in a cycle of exploration and refinement. When I look at Ryman’s work, I often get the sense that it contains the whole entire history of painting within itself, while also standing somehow outside it – it would be overstating the case to say SHM II does the same thing in relation to music, but I don’t think it’s overstating the case to say it points towards the possibility. The difference, of course, is that Drumm is not working in shades of white. There is no lightness here, but rather a crushing weight. Not the clouds but the abyss. Not heaven, but hell. But as paint is just a material, so hell is just a place, so pain is just a sensation, so noise is just a sound.

adore your dedication to writing about noise music in a way that is not technical to an impenetrable degree (pedal jargon) nor overly flowery and descriptive. concise and considerate to the state of contemporary noise