The Cathedral (2021)

Some thoughts on a new film which wishes to be a bit older.

We see a table set with plates, glasses, fresh tablecloth in front of a large mural of a seaside town. There is a cut, to somewhere else, something else. Then, we see the same scene, except a waiter is still in the process of setting down the glasses which we have just seen, impassive in two neat rows, in the shot before. This is the heart of The Cathedral’s technique, although it is rarely this direct: a muddling of chronology, a fixation on incidental details over consequential events, a certain distance, as if everything we are seeing has already happened, even as it occurs – in this manner the film manages to embody the fickle ephemerality of memory with uncanny accuracy. A period piece which covers the late 80s to the late 00s, in which two women painting their nails in a bedroom serves as the emotional climax, and 9/11 is just another school day, scarcely mentioned at all.

There are many figures like the aforementioned waiter in this movie: discreet hands which deliver food, take it away, sweep up what’s left over when a glass is broken. In this way the film says indirectly what would be too vulgar to be direct about: that regardless of their actual financial solvency at a given moment, the families within which the film is embedded see themselves as entitled to a certain degree of bourgeois comfort. They are people of a certain class, accustomed to being this class, comfortable with it to a degree which makes them oblivious to it. Business ventures are more or less successful, futures appear more or less bright, but there is never a question what is beneath consideration. For the filmmaker within the film, who is, it seems, somewhere between a character and an idea one convinces oneself of, the video camera he is given at 13 is a way to “finally bridge the gap” between the world and himself. We are not told why the gap exists, but we can guess.

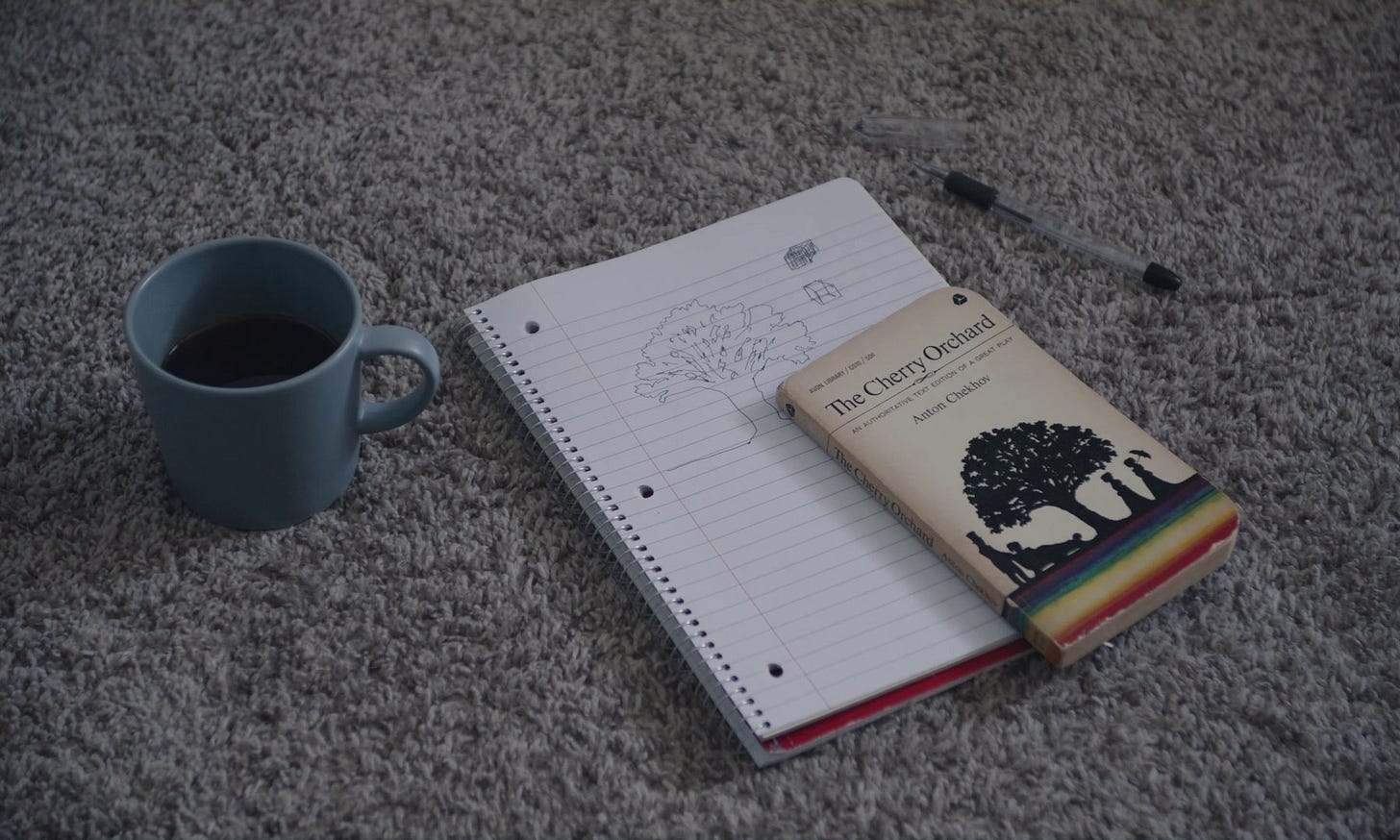

The film is full of tableaux too casual to be real and too composed to be fake – a cup of coffee, a Chekhov book, a woman sitting inside, framing two of her daughters on the patio behind her. We know there is a degree of autobiography at work here, because the nucleus is a filmmaker, and a film about a filmmaker is always a form of masturbation, and masturbation is always a form of autobiography. We do not, cannot know how much is recreation and how much is fabrication, but we know both are present, and thus they become the same. Restaurant silverware is dirty, because the child’s uncle died of AIDS. It’s not that the lie becomes truth, it’s that the world becomes part of the lie, as it always does.

d’Ambrose edits like his shots are polished marble slabs – heavy, solid, definite, but not to be scratched. A cut is never casual, it is always a decision, and always final; nothing is built easily. The child looks through a book detailing the construction of a cathedral through exactingly detailed ink drawings. The last page shows it towering over a city of simple dwellings, a couple stories high at most. The disparity is orders of magnitude greater than what we are accustomed to in the 20th century – there are no Great Works anymore, or there are too many, which amounts to the same thing. Each skyscraper diminishes the others. Thus why we see nothing but a few rooms, a gaze averted, a light on a carpet, a cold face at a funeral. It is all very little and, curiously, it all amounts to only a little more than that. Most films today pretend to be much larger than what they are, or smaller. The Cathedral is a rare example of one which is almost exactly the size it appears to be. Like a Lichtenstein painting, it derives its drama from the small difference between a solid color and a dot matrix. There is a gap, it is being bridged, we are not the ones crossing. This is both a strength and a weakness, to the extent that it would be wrong to call it either. Like most things in the film, the point is simply that it is there, that we see it, that it has some sort of existence. Emotions exist, too, and sometimes we feel them, but they are happening somewhere else. Not on the screen.