Minor Horror #02-14: Burial Ground

This is the fourteenth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this.

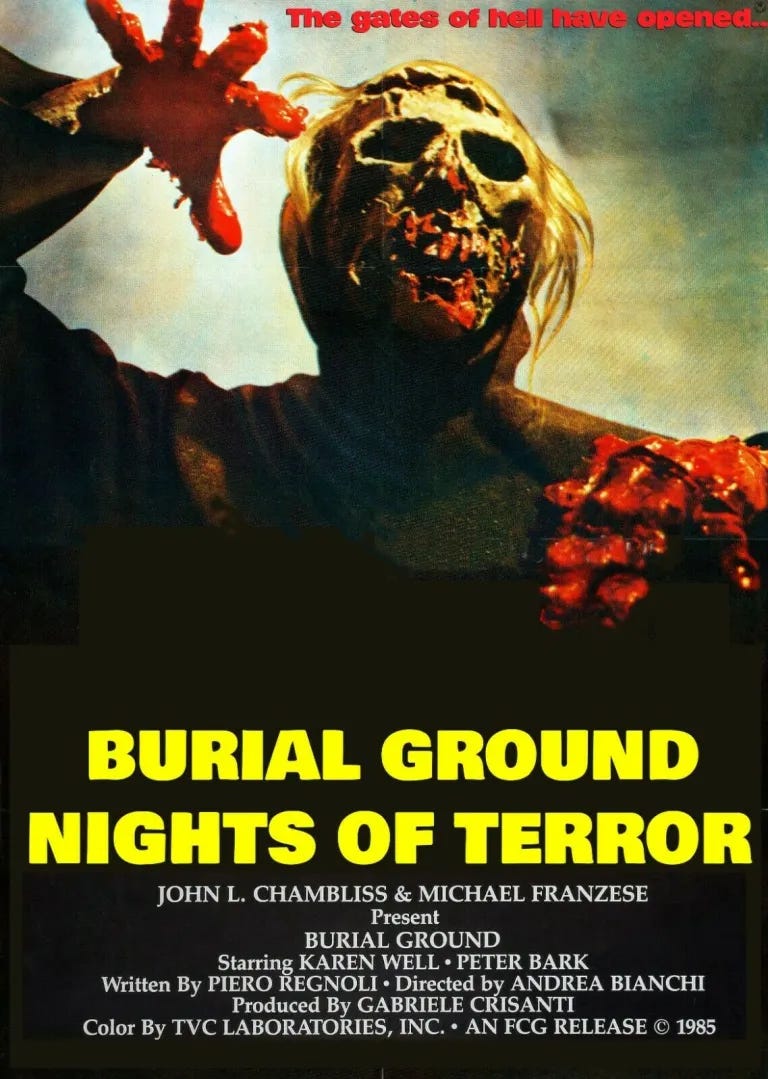

Burial Ground (Andrea Bianchi, 1981)

It is very important to Burial Ground that you not forget that a zombie is made of dead flesh, reanimated, and that this flesh has been rotting, and is still rotting. This is not always the case, in a zombie movie – of the classic movie monsters, they are certainly among the most basic, the most conceptually straightforward, and therefore among the most commonly loaded with some symbolic function (zombie as consumerist, zombie as dogmatist, zombie as disease-carrier, etc.) which takes narrative precedence over attention to the materiality of undead-ness. In this regard they are likely surpassed only by the “ghost,” a figure which, notably, does not conventionally possess a corporeal form at all. Even in cases where the zombie is not performing any particular symbolic or allegorical purpose, it’s often there as a monster of convenience, so to speak, a low-level threat for a film’s characters to deal with in addition to more serious ones, or just the thing outside that means they all have to stay holed up and start showing their psychological cards to each other, and to us. Not here, though, not in Burial Ground. In Burial Ground, the point of the zombies is entirely themselves, their materiality. They do not symbolize anything, they are not just a means to some other end; they are dead, rotting flesh reanimated, and they are out for blood. It’s true that in this movie our characters do, at one point, hole up together to try to resist a siege, but we don’t really learn anything new about them in the process. They just spend a while barricading themselves, then trying to hold the barricades, then getting overrun and fleeing. Very little conversation happens, none of it very meaningful. Really, everything there is to know about the living people in this movie we’ve already learned well before this point in the narrative; they’re all very shallow characters, possessing one, maybe two traits apiece, because this is not a movie about them. This is a movie about zombies. There’s a professor with a wizard beard deciphers something or other, this makes him go into some tomb and break some ancient seal, this causes the dead to rise, they kill him. Some carfuls of couples show up at the villa where he was staying for some rest and relaxation. There’s maybe ten or fifteen minutes of them settling in and screwing each other, not seeming to care the professor is nowhere to be found, then the dead attack and that’s it. That’s the entire setup. The rest of the movie is zombies.

Burial Ground is an Italian production from the near the tail end of the period where Italy was producing some of the most remarkable and groundbreaking horror cinema in the world. If you’re reading this, you’re probably at least vaguely aware that this moment was defined, arguably, on the one hand, by directors like Bava, Argento, or Fulci, who were genuinely brilliant artists, and who found ways of making commercial horror cinema into a vehicle for the exploration of their own personal obsessions and perversions, and, on the other hand, by directors like D’Amato, Mattei, or Lenzi, who were not genuinely brilliant artists, but were completely unapologetic sleaze-peddlers, and who also tended to cram their horror films with weird perversions, because weird perversions sell. I am laying out this schema because I think it’s important to understand that Andrea Bianchi belongs unambiguously to its second category, to the sleaze-peddlers. If you have heard of him for anything other than this, and you’re not a serious connoisseur of Italian sex films, it would probably be the giallo Strip Nude for Your Killer or the gangster flick Cry of a Prostitute – I haven’t seen either of these films, but I’ve heard of them, and I could see myself watching them one of these days, which is not nothing. Beyond that, it’s a pretty uninspiring list of credits, to put it bluntly. I’m sure his deeper cuts have their moments, but I think that’s all you could reasonably hope for, in choosing to watch them: moments, and nothing more.

I don’t find this lack of depth in Bianchi’s filmography surprising, even though I think Burial Ground is a very good movie, because a lot of what I like about it, and this is the same for much of what I like about D’Amato, Mattei, or Lenzi (although Lenzi is a slightly weirder case, I suspect; further investigation needed…), comes from its blunt artlessness. This is a movie about the dead rising from their graves and attacking people, and so this is what happens in it: the dead rise from their graves and attack people. This happens basically continuously for over an hour. It is the least “imaginative,” most direct realization of its premise imaginable. Part of how the movie is able to stretch things out for as long as it does are the usual narrative contrivances, characters separating and regrouping, having to move from one location to the next, things like that, but mostly it is because Bianchi simply allows the camera linger excessively on these zombies, again and again. He holds on closeups for long enough to make sure we can take in every maggot wriggling on the discolored flesh, appreciate every grotesque deformity which decay has wrought on the features, holds on wide shots long enough that we can pick up on the particular nuances of each zombie’s clothing and movements, its uniquely shambling gait. Whenever one of the things gets its head split open, ample time is given to make sure we see all the goo and pus and viscera slop out, the same with any bullet or puncture wound. None of these shots are particularly well-framed or well-lit, but they’re not particularly poorly-framed or poorly-lit, either. They’re functional, almost utilitarian images, and yet their subject is, again and again, something deliriously, absurdly, comically grotesque – and this is why the film works, why it’s interesting, why it feels so fucking bizarre. It shows you absolutely insane things with a completely flat affect. It shows you a corpse with its nose blown off and little writhing grubs in its eye sockets like there’s nothing special about such a face. The corpse rips a huge flap of skin off a screaming man’s neck, and the camera looks at it like this happens every day. There is no investment in the images, no emotion, no drama; everything is right there on the surface, everything is exactly as it appears. There are zombies. They are dead. They are killing the living. Time has made them rotten and decayed and hideous. It will do the same to you, if your body lasts long enough. That’s all there is to it. There’s nothing else to understand. There’s no other way for things to be.

There is one, and only one, very minor subplot in the film, involving a boy and his mother. The boy is very strange looking, one of those children who somehow already appears to be elderly. Something about the way the skin is stretched over his skull. He has an extremely obvious, extremely severe Oedipus complex. His mother has come on this trip with her new man, who is not the boy’s father, of course, and who the boy hates, of course. On the first night, he catches them in bed together, and is horrified. None of this goes anywhere because the zombies attack the next day, and the new man is the first to die, because this isn’t a movie about human psychology. This is a movie about killer zombies.