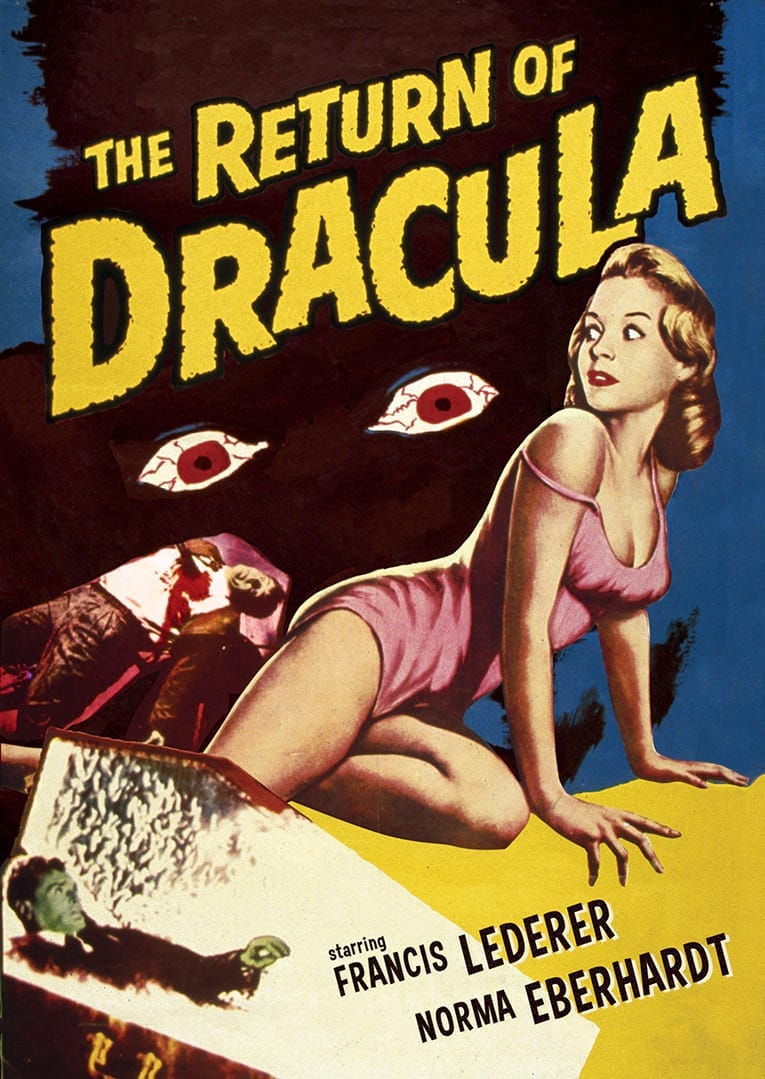

Minor Horror #02-15: The Return of Dracula

This is the fifteenth and final in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this. Happy Halloween!

The Return of Dracula (Paul Landres, 1958)

“Life is filled with goodbyes.”

The cat mewing in the open pit. The smoke billowing in through the open window. The cross left on the side table. The girl who wants to be a dressmaker. The relative from the old country, who traveled across the ocean, who’s looking for “freedom,” whose smile is wide and indulgent, but which never quite reaches his eyes. He brings death, he brings unlife, the frail woman in the bed becomes a figure in the distance, on the other side of the train tracks, becomes a snarling dog. The dog is white as snow, as a burial shroud. He wants to make the girl who wants to be the dressmaker into something like that, too, as he always does. Evil, sin, corruption. “He can become almost anything,” says the man hunting him. The inverse is true as well: other things can become like him.

This is a movie about a small town, the kind of town where everyone calls the priest “Doctor” and people almost always die from natural causes. The model is Every Town, USA, white-picket kitsch, Jesus and apple pie, but something is different about it, somehow it doesn’t look quite the way it should: the shadows are too heavy, too numerous, the day always seems to be sliding towards night. People always seem to be out later than they planned to be, later than they should be, getting strange impulses walking home, veering off into the grass, over that rise, towards the old mine entrance, the open pit. All good people, of course, honest and God-fearing, but there is something twilight about their town that they don’t seem to notice, something tinged ever so slightly with a soft shade of menace. A nice place to live, perhaps, but again: so full of shadows. It seems like there’s hardly ever anyone getting off at the train station, and perhaps there’s a reason for that, perhaps most would prefer to be in a place where the sun doesn’t fall down behind the hills quite so quickly. And the family, the family with the relative from the old country: a mother, her daughter, the would-be dressmaker, and her son, who’s still just a boy in a Devil mask, who loves his cat. What do you notice about this? There’s no father. He’s missing. The mother says she’s so glad there will be “a man around the house again.” But what happened to the old one? Are you sure this one is such a good replacement, with the way he keeps looking at your daughter? It’s getting late. The Doctor had better be getting home.

This is a movie about a vampire, and the vampire might be Dracula, but he might not be, as well. It’s confusing, because if you look online, that’s who the character is identified as, but the credits on screen don’t specify roles, and he never uses the name in the movie itself. References are made to the “Dracula legend,” and to the men hunting the vampire as “hunting Dracula,” but the whole problem with Dracula, the whole reason he needs to be stopped, is the way he spreads his disease, makes others into things like him, and it’s never quite clarified that it’s really the Count himself who gets off the train in this town, and not some other vampire, instead. And he doesn’t quite seem like Dracula, anyways: he has the right accent, certainly, but with his curly quiff and penchant for melancholy digressions he seems more modern than that, a man who might have been born in the early 19th century, not the early 15th, as Stoker’s book speculates. This vampire, whoever he is, lives the life of a man on the run, that much we know; if he was a Count, and did have a castle, he’s lost it by now. Perhaps in the war. We first see him on a train, peering over the top of a newspaper, in classically fugitive fashion. That’s where he meets Bellac Gordal, the real man, the real relative from the old country, a painter leaving home for America, it’s implied, because there he will be free to paint as he wishes, and perhaps this is even true, at this time, relative to this place. He seems like a good man, and perhaps he could have found great success in the New World, if he hadn’t chosen to sit in the train car he did, the one occupied by a creature in need of a new identity, and with no respect for the sanctity of life. But he did, and so we will never know.

This is also, almost incidentally, a movie about Halloween. The timeline is a little vague, like many aspects of the narrative here, but the vampire arrives in the town sometime in late September or early October, and things come to a head on the night of the big Halloween party. You might not realize this, given how inextricable ’50s Americana kitsch is from contemporary Halloween aesthetics, but it was actually very uncommon for a movie of this period to make the holiday a significant plot element. It’s not unprecedented, it figures in I Was a Teenage Werewolf and, maybe you’ve heard of this one, Meet Me in St. Louis, but it wouldn’t be until the slasher era that the idea of incorporating Halloween itself into the sorts of movies people might want to watch around Halloween really took hold. The Return of Dracula was ahead of the curve in this regard, which you can sort of tell because it doesn’t really know how to incorporate it. There’s no real build-up to the party, characters just suddenly start talking about it and then it happens. Nothing even happens at the party, which is, in itself, to be fair, a nicely realized bit of small-town coziness, old spinster ladies tacking up ghouls and hanging cobwebs on the walls of the parish, punch and a costume contest, and seemingly half the attendees wearing pieces the dressmaker-daughter designed and fabricated. But no, nothing happens there, rather its function is to be a warm, safe place, a place of family and community, which the vampire has to draw his prey away from in a sort of waking trance. Anything of real darkness must happen somewhere else, somewhere lonely, somewhere away from prying eyes – only there can the promise of living forever, of witnessing everything you have ever known die and rot and crumble away while you persist, while you tread upon the dust as everything you have known returns to it, might be whispered like a seduction in an innocent’s ear. Halloween, in 1958, has no part of things as unholy as this – it’s a day in good standing, all in good fun, a bit of light blasphemy perhaps, but nothing as perverse as the open pit, the fugitive on the train. But that’s starting to change. The mythology is evolving, becoming more elaborate, more subversive, expanding to accommodate the imaginations of older children, teenagers, young adults – people who know what sex is, in short. And this is not happening for no reason: it’s happening because of movies like this. Halloween is becoming like him.