Minor Horror #02-4: The Black Door

This is the fourth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this.

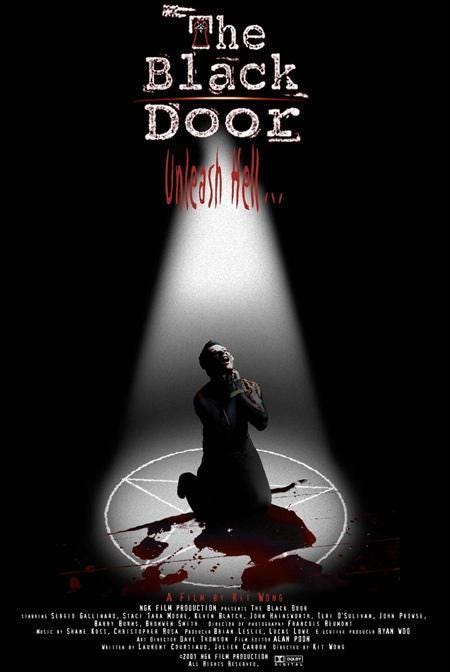

The Black Door (Kit Wong, 2001)

The Black Door is a surprisingly ambitious blend of found footage and faux-documentary techniques, a movie about a Mexican businessman who disappeared in the 1930s but set in present-day Seattle, directed by a Chinese woman, and written by a duo of French expats living (at the time) in Hong Kong, whose only other writing credit (at the time) was the also very strange and twisty Johnnie To thriller Running Out of Time. I’m opening with this information because the bizarre, multilayered cultural/spatial/temporal dissonance present here goes a long way towards explaining the first thing you will notice about this movie, which is that everyone in its faux-documentary scenes talks and behaves like space aliens trying to pass for ordinary humans, or as my colleague Astrid Rose astutely observed, “like characters in a point-and-click game,” which is basically the same thing. Even on the rare occasions when a character says something it makes sense for them to say in the abstract, they will say it in a way that’s completely insane – even a generic news report about a car accident manages to sound somehow just off enough to feel completely wrong. I think it’s good to know this going into the movie, not only because it will completely throw you if you’re not expecting it, but also because if you are, if you’re willing to take it as it is and go with it, you’ll find that in a lot of ways, it actually serves to amplify the uncanny, off-kilter energy of the rest of the film. The Black Door is the sort of thing where you’re constantly not quite sure how seriously you’re supposed to be taking it, but the fact that you’re unsure only makes it creepier, because if this is a joke, it’s a pretty sick one.

It’s hard to know where to start with this movie. It more or less drops us into the middle of its story and then starts switchbacking like a mountain road, filling out the background while also climbing towards the conclusion. There’s also the small problem that what exactly the film seems to be, diagetically, keeps shifting. It’s one of those slippery, ambiguously metatextual sort of movies, where every time you think you’ve pinned down exactly what it’s doing, it’s suddenly somewhere else, suggesting something else entirely. But okay: I guess we can reasonably say there’s a man in a hospital. His name is Steven. There are deep, horrible cuts all over his body. He has some sort of infection, apparently unknown to medicine, that’s eating him away from the inside. Then there’s the businessman, who he was researching (he’s a PhD student, who was working on US-Mexico trade in the ‘30s; it’s another one of the notably idiosyncratic and unsettling details of this movie that its PhD student was studying something without a hint of exoticism, the banal specificity of which feels both deeply contrived and plausible enough to suggest that the trap he’s fallen into could lie around any historical corner). The businessman was (is…?) named Balmaseda. Steven, looking through Balmaseda’s old ledgers, discovers some strange, very large payments Balmaseda was making to three men in the last years before he disappeared. He suspects blackmail, but then he finds a reel of 8mm film. We are shown this reel in its entirety, broken up into segments to build suspense, with intrusive, bluntly literal narration that sounds like AI, even though this came out in 2001. Documented in great detail on the reel is a Satanic ritual in which, with the help of the three men he was paying, Balmaseda offers himself as a willing sacrifice to a demon. He bathes in a tub of blood, he drinks something that makes him delirious, the men kill him, he collapses into the pentagram they’ve prepared on the floor. As pseudo-snuff, it is abnormally convincing, not because the effects are spectacularly “realistic,” but because it feels genuinely abject, all that elaborate ritual preparation culminating in a body twitching on the floor of some dismal, cramped room, soiled by its own fluids, lying there slowly decaying – because that’s what happens, you see, it is left there for hours and then days, as the men wait for something to happen. What, we don’t know. After many hours, something does happen, but not much, nothing that seems worth the price. “Was this what the men were waiting for?” The narrator asks. Cursory investigation determines the three other men all died as well, and violently, within just a few years of the ritual. It doesn’t seem like they gained much from it, either. It is around this point that you will really begin to wonder what exactly it is you are watching. Things are not quite unfolding in a familiar way.

There is a second major found-footage set piece in The Black Door. This one, filmed, bizarrely, by pointing a camera at a television screen playing the tape, documents Steven exploring a house where one of his “contacts” has sent him. Unlike the 8mm, this is shown in one mostly-uninterrupted chunk. If most of the film is like a point-and-click adventure, then this segment is like a survival horror game, with Steven walking around an apparently-abandoned house, which he doesn’t hesitate to break into when he finds the front door locked, using his camera as a light (it’s the middle of the night, of course). This goes on for a discombobulating amount time – I had totally lost track of the internal geography of the house well before it wraps up. There’s no voiceover narration, leaving it up to Steven himself to react to every weird thing he finds like a Silent Hill protagonist trying to nudge the player towards the solution to the puzzle – except there isn’t a puzzle here, not really. Or, I mean, there is, but it’s not here, exactly, it’s somewhere else, hiding in plain sight. We haven’t quite been clued into it yet, but we will pretty soon, when the documentary crew (along with a priest who I haven’t talked about because I don’t even know where to begin with him; I’ll just say that when he’s on screen is when it most feels like the movie is fucking with us) goes to meet this “contact,” played by John Hainsworth absolutely devouring the scenery in a small but crucial role. His performance is actually the only convincing one in the movie (outside the ritual footage), not because he sounds anymore like a real person, he doesn’t, but because his character, we realize, can hardly be considered a person at all, in most of the ways that count. He’s kind of like one of those Saturday morning cartoon villains that got written a bit too intense for the target demographic, except here the target demographic isn’t schoolchildren, and John Hainsworth isn’t (quite) a cartoon. In contradistinction to the priest sitting right across from him, whose whole character feels like a joke the movie is playing on us, when the (diegetic) filmmakers give him a nice big closeup to stare right into the camera, right into us, we suddenly realize we’re in this deeper than we thought. Once again, as with the Satanic snuff film, we feel a bit of genuine unease, a bit of credible menace. That the movie is not exactly able to sustain this feeling does keep it well off from achieving greatness – but on the other hand, this very inconsistency, combined with what Hainsworth’s character seems to suggest about the movie itself in his one big scene, in a sense just underlines the deep, destabilizing wrongness the movie has possessed from the very beginning. There is a sense in The Black Door of glimpsing something truly scary, but only obscurely, only for a second, a sense of something emerging from the fog and then, before you can really figure out what it is you’re looking at, disappearing again. This is, I want to be clear, on a certain level the product of a dramaturgical weakness, a real failure of the film’s narrative structure. It is also, however, one of the most important things a horror movie can do.