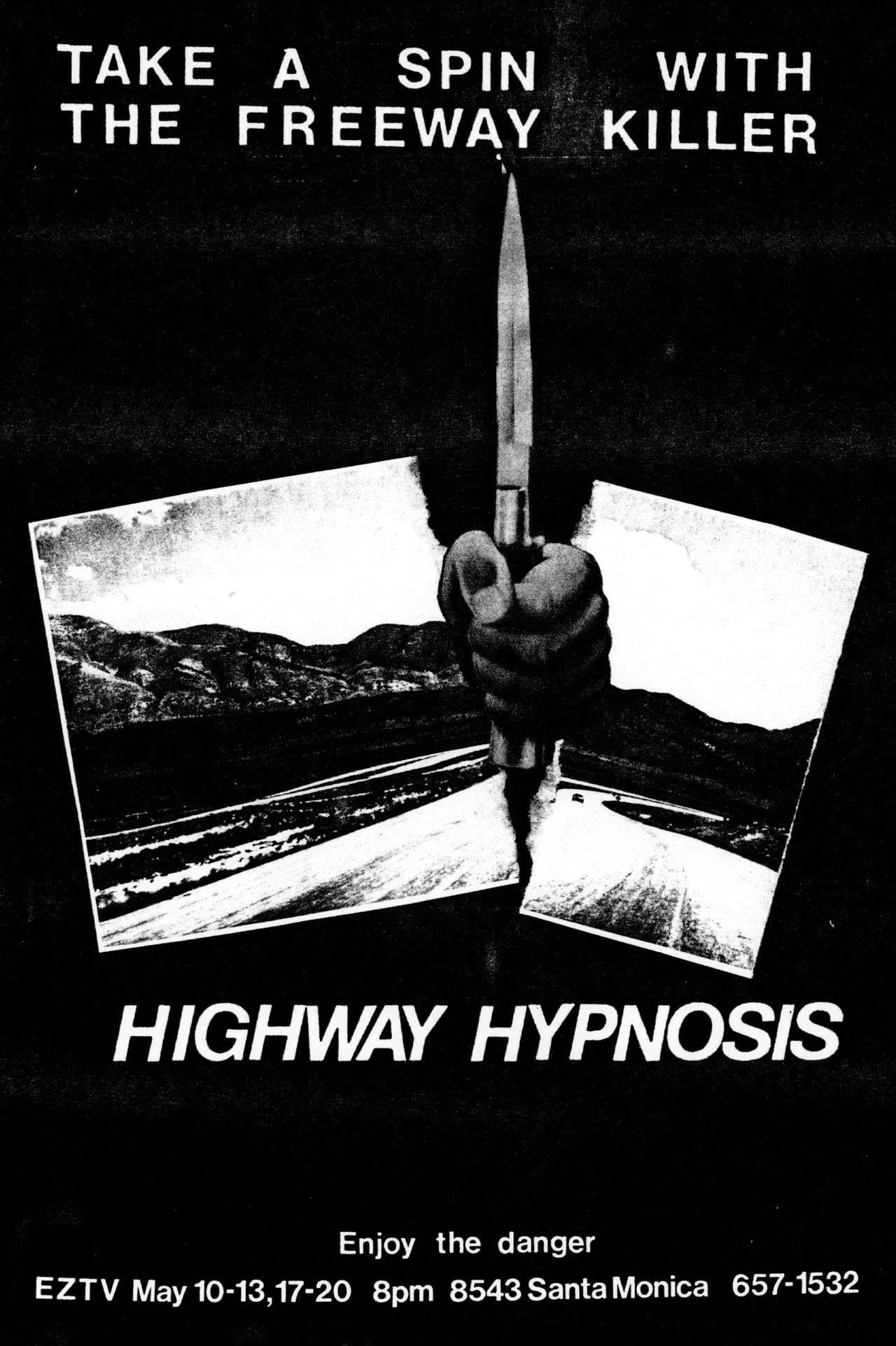

Minor Horror #02-5: Highway Hypnosis

This is the fifth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this.

Highway Hypnosis (Ken Camp, 1984)

It’s reported that William Bonin’s mother would pray for him. It’s reported, as well, that she would often leave him and his siblings alone with her father, who was a child molester. She knew this about him, having, in her own childhood, been one of his victims. Bonin also spent a lot of time in various institutions for delinquents in his early years. It seems he was abused at all of them, by authority figures, other children, or both. The abuse was usually sexual in nature, but sometimes it was purely sadistic. When he got a little older he joined the Air Force, where he served as an aerial gunner in Vietnam. He would later claim that his time in the service “instilled misanthropic beliefs.” He was once awarded a medal for gallantry. Before he went overseas, he had gotten engaged to a woman named Linda, although he really preferred young boys. When he got back, with an honorable discharge, he found out she had left him and married another man. He got a job at a gas station, moved back in with his parents, and started driving his mother’s car around, picking up teenagers, beating them, and raping them. This led to an indictment for crimes including sodomy and oral copulation. He spent a few years in and out of prisons and mental hospitals for these and similar offenses. In 1979, he started killing the boys he picked up, instead of just raping and torturing them. He would leave the bodies by the side of a freeway. He wasn’t the only one doing this: there were at least two other men, men named Patrick Kearney and Randy Kraft, who were murdering boys and dumping their bodies near the California freeways around this time. They weren’t working together; they had never even met. They just all had the same kinds of ideas. A sign of the times. Before they were caught, it was imagined that it must be just one man killing all these boys. The media started calling this man the “Freeway Killer.”

You will not learn any of this information from Highway Hypnosis, which came out a year after the last of them, Kraft, was captured. I had to look it up myself to try and get a handle on what I was dealing with. Highway Hypnosis is a movie about a nameless man identified as “Freeway Killer” in the end credits, and nowhere else, because he never says anything to anyone, and no one ever says anything to him. This man is not William Bonin, or Patrick Kearney, or Randy Kraft – he drives a different kind of vehicle, he has different sorts of habits, and the actor playing him, Leonard Lumpkin, doesn’t look especially like any of them. What these men are, for Highway Hypnosis, is a ground, a setting, a necessary precondition. This movie’s Freeway Killer is not any of the real Freeway Killers, but he does not exist without them.

In Highway Hypnosis, the Freeway Killer goes for a drive. He drives from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. He meets a young man there and he kills him (off-screen; at first, we think that he’s sleeping, or pretending to sleep). Then he drives back from Las Vegas to Los Angeles. That’s it. Most of the movie is shots of him behind the wheel, driving, or shots out the passenger window, or looking through the windshield, watching the road ahead. The video camera that shoots all this (because this is a shot on video movie) is handheld, and often unsteadily. In 1984, these things would still be pretty heavy, pretty bulky, hard to handle. It awkwardly tracks people waving out of passing busses, or wheels around to catch a woman getting out of a sports car while the Freeway Killer is parked in Las Vegas, reading a roadmap. We get a small sense of his home life, but only a small sense: peering through the blinds at his neighbors, sitting in a camping chair in an otherwise-unfurnished room, watching TV, drinking a beer, just wearing underwear. Cars on the TV, music, whatever. It doesn’t make a difference. Classic going-nowhere bachelor life, more than a little reminiscent of another character study of a boring loser serial killer from the period, the very underrated Murderlust (1987). But where that film stayed grounded in the mundane grind of its schlubby misogynist killer’s shitty life, Highway Hypnosis is an altogether more elusive, metaphysical prospect. I’ve just implicitly described it as a character study, but it would maybe be more accurate to say this is a character embodiment, an attempt to put us into a particular headspace in a very direct fashion. There’s no explanations here, no “insights” per se – what there is instead is shot after shot of cars, buildings, mountains on the horizon, the road stretching away ahead, baking under the indifferent sun. Then, sometimes, there will be something else, a sound, an image, a flash of light. There will be something wrong, something different, bad, blood poured down a drain, the teeth of a saw digging into an arm, what seems like the inside of a womb, or a rectum. These things never last for too long, they never get literal enough to resolve into anything definite. And then it’s the road again, the cars, the desert, a park, a casino, ordinary places, nothing going on, nothing to see, a jogger runs past, an old woman takes on last drag of a cigarette before she gets on the bus. Inside the mind of the Freeway Killer, the movie’s Freeway Killer, that is, to be clear, who can say about the real ones, probably no one, probably not even God, but for this Freeway Killer there’s some relationship between these things, the one feeds into the other, the other feeds into the one, they aren’t separable, they aren’t even different, they’re both the same thing, which we know even though his face remains impassive, because we’re not really looking at his face, we’re behind his face, we’re inside of him, he’s inside of us. Then the movie’s over, and we snap out of it, and we wonder why we ever thought such a thing. But of course, this is how hypnosis works. What’s unnatural will suddenly seem like the most natural thing in the world. The same principle lies behind prayer.