Minor Horror #02-7: The Haunting of Rosalind

This is the seventh in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this.

The Haunting of Rosalind (Lela Swift, 1973)

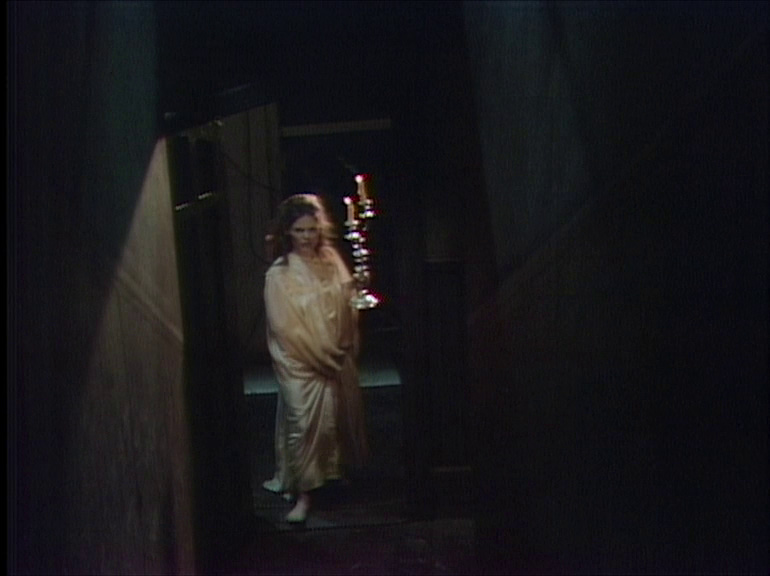

There’s a certain distinct pleasure to watching things shot on early commercial videotape. Its particularities are unique and unmistakable. The texture of the image has a muted vibrancy to it, a sort of soft, throbbing intensity, quite unlike the sharp lucidity of 35mm film. The edges of things are not quite clear, not quite definite; it feels like any pool of color could overflow its boundary at any time. Things feel palpable, physical, like they could get “stuck” to the frame somehow, like syrup on glass. Even professional productions in highly controlled studio settings are never quite able to eliminate the ghostly smears left behind by every passing light source. It’s an aesthetic register strongly associated with television of a certain vintage – especially with daytime television, soap operas and whatnot. Even today, sit down and watch a bit of one of the major network soaps today and you’ll find, if not the same register, then its direct descendant, something imbued with the same strange, spectral physicality, the same kind of artifice, so unlike the artifice of the Cinema, then or now. But, of course, it wasn’t only soaps that were shot in this way. There was also, among other things, The Haunting of Rosalind.

The Haunting of Rosalind was one of five television adaptations of Gothic horror stories produced in 1973 as a series called The Classic Ghosts. Recordings of these (live!) teleplays were, for decades, either entirely unavailable or only in extremely suboptimal forms, such as a black-and-white telecine of The Screaming Skull sourced from who knows where, but then UCLA restored them, and Kino Lorber released those restorations as a two-disc Blu-Ray set last year, making them trivially accessible, and in pretty much the best quality one could hope for. When I was first working my way through them (because obviously this is the sort of thing I would be interested in), I had some ambitions towards writing a piece about the whole series – ultimately, though, they turned out to be neither consistently interesting nor consistently idiosyncratic enough that it seemed worth the effort. Cumulatively, they’re a neat set of stories, reasonably engaging, and representative of an interesting moment in televisual history, which is to say they’re well-suited to the careful attentions of an earnest and circumspect media historiographer, and that’s not me, not these days, not anymore. But of course, I didn’t entertain the idea for no reason. The first one I watched was, in itself, interesting enough to warrant serious consideration – and that one, as you might have already guessed, was The Haunting of Rosalind.

One of the (many) interesting things about Henry James is that, despite so much of the pleasure and wonder of his writing being found in its stupendous compositional density, in the way the experience of reading him is akin to wading through a vast sea of textual brambles, each comma or semicolon as if yet another thorn, it tends to adapt to film quite well. I think this is because, and I hope this isn’t too controversial, he came up with a lot of good stories. It was his ability to write those stories into great, dizzying linguistic edifices that made him one of the Greats, of course, but I think it’s reasonable to say that it probably helped that those edifices were so often built upon such abnormally subtle, clever, perceptive, and compelling little tales. All this to say, the first sign that The Haunting of Rosalind is of special interest is the fact that it’s a Henry James adaptation. And, being a live teleplay, it’s an adaptation of significantly limited means – this is also a good sign; the less “production value” a period drama has to work with, the more it has to rely on the strength of its actual drama, which is, when we’re talking about James, at least, the real substance of the thing.

The Haunting of Rosalind is adapted from James’s short story “The Romance of Certain Old Clothes,” which I haven’t read, but as far as I can tell it seems generally faithful while making a few important changes. The broad thrust of things is there are two sisters, the one (named Dita) young, easygoing, and voluptuous, the other (named Rosalind) young, nervy, and gaunt. Their brother brings home a handsome friend one day, and both sisters fall for him, despite lingering questions around what exactly happened to the man’s first wife. Although he entertains the affections of both sisters, and at first even seems possibly more drawn gaunt and nervy Rosalind, he eventually makes the choice everyone in the family expects him to make, and marries Dita instead. Although each sister had vowed not to be jealous of the other if they were chosen, that is, of course, not how things work out.

If it wasn’t obvious, this is, like many a James story, a story about sexual repression. Rosalind is what would be called a “femcel” today, lonely, shy, emotionally stunted, smart enough to recognize this is not the life she wanted but hopelessly lacking the self-confidence necessary to actually do anything about it. She’s prone to magical thinking and hysterical crying – a classic case of “nerves,” as they used to say. One suspects it would do her a lot of good if someone would just sit her down and explain how masturbation works, but, of course, the whole problem is she was born into a time and a place where that would be unthinkable. It’s notable that although this is a house full of women, the dead father is still patriarch, his stern-eyed portrait hung in a place of prominence, where it can watch over everything in the house. Its eyes often seem to burn especially intensely into Rosalind, and there is an incestuous subtext here, all the more perverse because it’s difficult to determine if she was actually abused, or simply desired to be abused – either possibility, of course, would go a long way towards explaining why she’s “like this.”

Were this all we were dealing with, this would already be a very strong character drama, classic James stuff – but, of course, there is something more. There is a ghost. What is interesting is it is not the ghost we imagine it will be. At first, in fact, there is no ghost at all, just the idea of one. This is one of those narratives where obsessive ideation turns a delusion, a fantasy, a kind of paranoid “cope,” into a real presence, an actual thing capable of action. I’m being intentionally vague here because it’s not clear what exactly the nature of this thing is until the very end, and it’s worth experiencing for yourself the way your expectations are played with. It’s very satisfying, because it achieves this effect not via a cheap twist which undermines or renders irrelevant what came before, but rather by withholding just enough information just long enough that you only come to realize at the very end that, yes, things really were as they must have been. It’s worth noting that The Classic Ghosts was a notably feminine project, with most of the creative team, including producer Jacqueline Babbin and, here, director Lela Swift, being women. The stories adapted in the series are not all particularly focused on “women’s issues,” as the term would be understood in the ’70s, but The Haunting of Rosalind certainly is, and I think much of its strength comes from how clearly it sketches these women. It would be easy to make Rosalind purely pitiful, or obnoxiously pathetic, or a kind of martyr to her own “hysteria,” but that’s not what happens here. Instead, she is allowed to be tragic, yes, but only so tragic. Swift, Babbin, et al., they know better. They know this sort of girl can be dangerous, too.