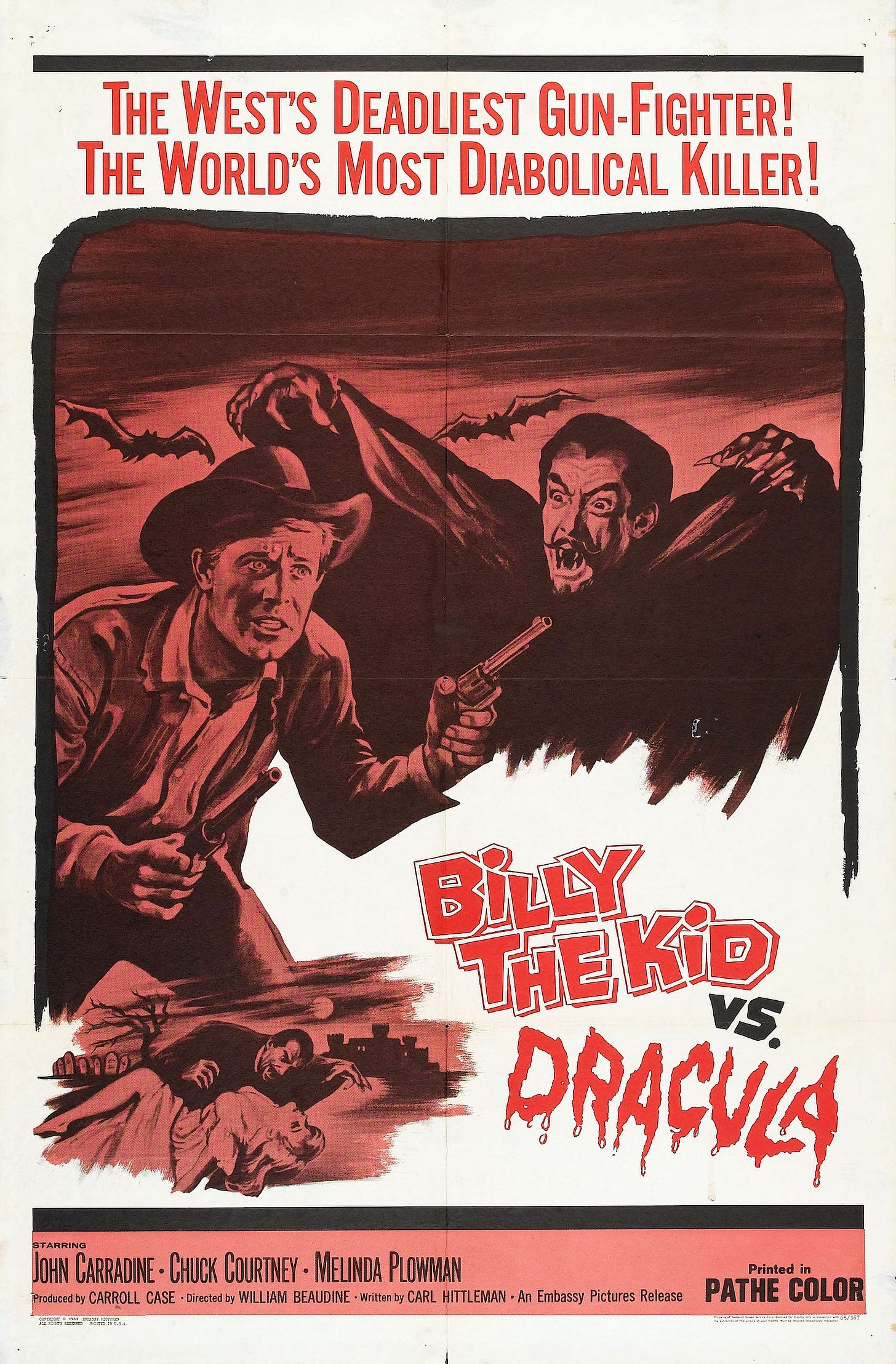

Minor Horror #10: Billy the Kid Versus Dracula

This is the tenth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post.

Billy the Kid Versus Dracula (William Beaudine, 1966)

Across his career, William Beaudine directed more than 200 movies. His first was released in 1915 or 16, a period in which he also worked as an assistant to D.W. Griffith on The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. This was his very last. It stars John Carradine, who, across film and television, has more than 350 credits. This was not his last; he would live another 22 years, and he would spend all of them working. He was a regular in Cecil B. DeMille movies, and those of John Ford; he was there, sharing the frame with John Wayne in Stagecoach, and he was there, two decades later, not sharing the frame with John Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (he was on Valance’s side, you’ll recall). By 1966, though, all that was over; his future was Vampire Hookers, Frankenstein Island, and (in a small, late grace note) Peggy Sue Got Married. The point I am making is that Billy the Kid Versus Dracula arrives at the end of something – whatever the value of a film like this, it was produced by conditions which were already becoming History.

Carradine plays Count Dracula, of course – or does he? He’s credited as such, and he’s certainly a vampire, but his accent is not Transylvanian in even the loosest sense, and to the best of my recollection, no one in the film actually learns his real name. He spends the entire time posing as “James Underhill”, uncle of the young beauty he wishes to make his vampire bride. Perhaps “Count Dracula” is just another facade, another disguise. He seems to come out of nowhere, a bat on a string flying towards a wagon train on a sunny day-night, and no particular attempt is made to explain how he got here, or why; surely it would have been an ordeal to transport his coffin so far. But this is a William Beaudine movie, so it doesn’t really matter. Perhaps he is Dracula, perhaps not; all that is relevant is that he is here, and that he wants Billy the Kid’s girl for himself. There will be some Indians on horseback, a skeptical sheriff, a sneering heel: all the usual ingredients of a western shot in a week, arranged in more or less the usual order. But then, also, there is this vampire running around, bumping into windows, looking evil lit in red from below, confusing everything, setting it off-kilter; the abandoned mine is still, in a sense, the outlaw’s hideout, but an outlaw who’s plotting a very different sort of crime, a crime against God’s law, as much as Man’s.

Beaudine is among the most artless of hacks, a director of movies in which every image is the most obvious – but this is what is interesting in a case like this, this is the heart of the appeal, that it is all so threadbare, so perfunctory, that no one involved seems to care, that it would all be forgotten within hours of watching, except for the fact that there is no other movie like this. Which is not to say it’s actually “entertaining”, of course; while it has its moments, it’s mostly quite dull – but this is the point. If it were played for high camp, as a parody of itself, the way movies with titles like this are today, it would be unbearably tedious, a complete waste of time. But Billy the Kid Versus Dracula is not a joke: it is exactly what it says it is. It is a movie where a western hero fights a vampire. It doesn’t really expect you to take this seriously, but it doesn’t really want you to laugh, either. Like all of Beaudine’s later movies, its only purpose is to follow one scene with another until enough scenes have happened that it counts as feature, and something resembling a story has occurred. It has no ambitions beyond that. It is not trying to make you feel anything. It just wants you to sit there and watch it. By 1966, they had stopped making directors like Beaudine, and they had stopped making actors like Carradine. Such men knew how to lie in the gutter with dignity, because they had come of age in an industry that behaved like an industry – that is, a question of labor and resources; a capable, experienced man, who took his work seriously, was worthy of respect, regardless of what that work was. Corman, of course, would adapt this model to great success, but he was the outlier. Cinema was beginning to be discussed as an art. And artists – in America, at least – deserve no respect.