Minor Horror #13: Season in Hell

This is the thirttenth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post.

Season in Hell (Elliot Passantino, 2004)

It is loud from the very start. It is chaotic and disorienting. It will not get better. Police cruisers shut down the highway. Bombs fall on the Middle East, white flashes in green night-vision. On grainy video, a man with his hands bound and a bag over his head writhes in front of a painted brick wall while another man holds a flame to an American flag and a caption tells us we’re looking at torture footage from Abu Ghraib. It’s not long after 9/11, not long at all, and the second terror attack of the week has just happened. America is dying, and its death will not be a quiet one. All this we learn in the opening credits. It is just setting the scene.

Two guys are making a break for the border. They grabbed the cash that they had and started driving north. They see the writing on the wall. Everything is breaking down, and they want to get out before they get broken, too. It was going well until Maryland, but then the money started running low, and now they’re almost out of gas, too. They’re on some middle-of-nowhere road in the northeast, deep in the stix, but that doesn’t make a difference: all the gas stations are closed anyway. The banks, too. They talk with each other about what to do. Neither of them seem particularly smart, just regular guys, early 20s, probably chill to hang out with, but definitely not equipped for this. Not at all. They’re in way over their heads. In this case, though, it’s easy to see there’s not many options: they can stop now, or they can stop another mile down the road; either way, their only hope is to find a house with some gas to spare. Ideally, the house will be abandoned – fairly likely, because who would stick around at a time like this? In another mile, perhaps this is what they would find. But instead, they stop here, at this house – and this house is not abandoned. In this house, there is work being done.

The man wears red and black flannel and speaks in an absurd caricature of a redneck drawl. He drinks cans of Coors and idly cleans an antler and tells the guys he used to have a wife, but not anymore. He seems entirely unconcerned about the state of the Union, about anything happening beyond his front door – it’s not that he’s ignorant, per se, so much as totally confident in his own security, as if assured of protection by some invisible force. He says he has gas he can give them, but he invites them to “take a load off” and spend the night there. For reasons even they themselves do not seem to understand, the two men agree. They must not have seen the weird face watching them from the home’s upper window. From this point forward, the film will explode.

I would estimate that for upwards of 90% of Season in Hell’s runtime, the image on screen will have been subjected to a filter of some kind – at least one filter; often there are more. When I say “filter” I do not mean anything advanced, or even tasteful; I mean the sort of stock, off-the-shelf plugin effects you might see in a YouTube video from 2009: fake film grain, sepia tone, garish bloom, tiling, hypersaturation, frequent usage of vertical mirroring, like in a Rorschach blot, and numerous chintzy wipes and dissolves between shots. These don’t, in themselves, really make the movie look “cheap” because the movie is, from the beginning, openly, unapologetically cheap, consumer-grade DV, awkward sound mixing, obviously nonprofessional actors shooting (probably) on a friend or family member’s house and property. iMovie-type effects aren’t breaking any sort of illusion here, so instead they serve solely to disorient, burying already low-fi images beneath further layers of distortion and abstraction, ensuring the film remains chaotic and disorienting even in those brief interims where the action itself is not its own kind of sensory assault.

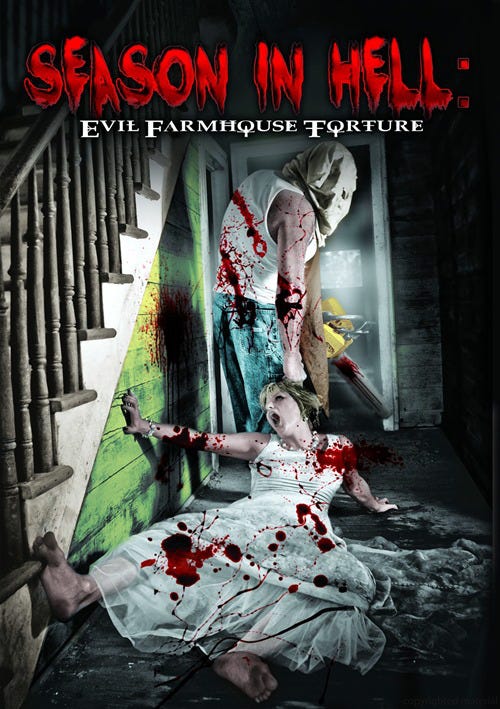

We spend a lot of time in a cramped, unfinished basement in this movie, and it would be easy to play up its claustrophobic monotony, but Passantino does the opposite, employing every trick possible to destabilize our sense of the space’s dimensions, cutting wildly between barely legible images until it begins to feel like an endless underworld populated by the damned – which is to say the women our homeowner abducts and tortures for his “work”, some of them still bound like the man at “Abu Ghraib”, others roaming free, willing accomplices operating, it seems, under varying delusions, varying relationships to sanity. There’s the girl who sits on the dirt floor in a white dress and veil, convinced that this is her wedding day; there’s the girl in the Spirit of Halloween Sexy Nun costume who fondles a crucifix and says things like “I need Father inside me”; there’s the first one the guys see, when they get up and explore in the night for, as far as I can tell, no reason, a girl lying at the bottom of the stairs so badly beaten they assume she must be dead, until she wakes up and attacks them. The exact nature of this “work” the homeowner is doing is never really made clear, but a few shots of a man with horns grinning demonically is enough to get the general idea. We watch a woman, hands bound to an overhead beam, being tortured by the false nun, smacking her face again and again with a wooden spoon. Later, though, when one of the guys comes and cuts her down, instead of being grateful, or exhausted, or trying to escape, she immediately jumps on him, knocking him down and demanding to know where her sister is as he tries to shield himself. This is not the only time something like this happens; all of the women seem to be aggressive, cruel, eager to make someone else suffer. Consider this in relation to a cyclical monologue the homeowner delivers about his own anger, and, psychosexually speaking, some sort of picture begins to emerge – although what exactly we’re dealing with never quite becomes clear.

Season in Hell is a movie which operates on nightmare logic through and through – no questions are answered; no choices are given; characters will go so far, sometimes, as to say they don’t know why they do the things they do. This is a strength, not a weakness, because it always means something. It is a form of narrative which takes the shape it does because it could take no other, because if it did not have to be this way – why would you ever allow it to be? In 2004, it was easy to believe America was dying. Today, it is even easier. Perhaps this is why the movie, despite being so clearly a product of its time, still feels, in some unshakeable sense, like a transmission from another mile down the road.