Minor Horror #14: Mask of the Red Death

This is the penultimate fourteenth in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post.

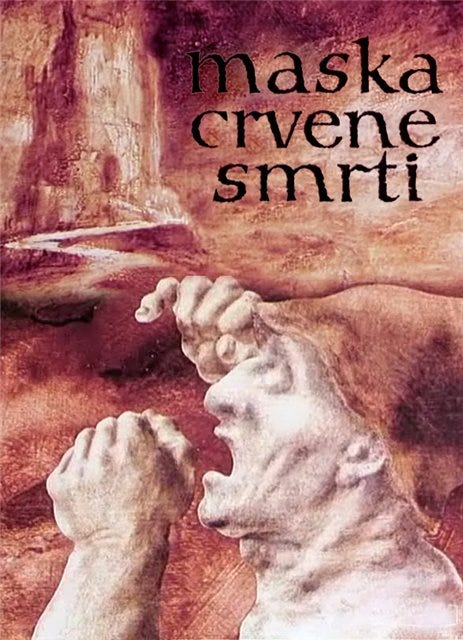

Mask of the Red Death (Pavao Štalter / Branko Ranitović, 1970)

The interiors of the castle look sometimes like flesh, like organs, brown, mottled, tumescent, stretched wetly across the frame like a map projection of some nauseous inner world. The Prince and his consort seem almost to disappear into it sometimes, as through dissolving in acid. Their features, like everything else, are crude, simple, weirdly smooth. They move in stiff jerks and marionette lurches. The jester ends his dance with a death’s head. Outside, the peasants lie dead in their fields. They die when a figure on horseback rides by. They die for no reason at all. They lie in twisted piles bleached white, and plumes of black smoke rise on the horizon, and blot out the sky. Processions of hooded monks disappear into baleful chapels, bells pealing, guided by shirtless men who lash themselves with heavy, woven cords. This is a world which has come to believe in its own annihilation, as an article of faith, as an observable fact. Only the most arrogant, steeped since birth in a cauldron of idiot power, idiot luxury, could believe that what has come will be stopped by a closed shutter, a raised drawbridge, a shut and bolted door.

The Prince and his consort would be almost pitiful in their doomed arrogance if there was anything about them that seemed human, anything that could be mistaken for people, for anything that is like you or I. Their faces are impossible masks, their bodies full not of life but some obscene, sneering parody thereof. This is the great strength, the great possibility of animation – its inhumanness, its falseness, its obsessive unreality. This is what makes it so well suited to Poe, whose work, at its most Gothic, is macabre in a way approaching the limits of patience, language, thought, all horrid twisting nightmares seen through warped glass, distorted souls writhing and contorting on the page, grotesque and baroque and teetering, tipping, tipping, on the knife’s edge of hysteria. I have a great fondness for the Corman-Price adaptations, all cobwebs and castles and long-simmering hatreds – but if one wants moving images which demonstrate a true fidelity to the texture and character of his prose, of his perverse, decaying genius, one must look elsewhere. One must look towards animation.

Štalter and Ranitović, to my understanding, animated this film more or less by themselves. It must have taken years. Their work resembles something like a Renaissance fresco, not as they would have appeared when new, but as they have been received, crumbling, sun-bleached, hard figures disappearing slowly into soft, silent ground. Equally, though, there is something to it that is like an advertisement, an illustration on a box of cards – not the sort that would be manufactured today, or in 1970, for that matter, but much earlier, the style of Old Europe, after Modernism but before the Great War, cultured gentlemen and ladies enjoying fine tobaccos, robust curatives in moody, dynamic half-abstraction. Perhaps this is what gives the whole film such an impossibly dreadful, doomed atmosphere: the sense that we are watching mannequins, wooden dolls performing as defunct archetypes, pantomiming the dusty shorthand of an ideal of wealth and leisure which died a long time ago, eyes rolled back in leaking skulls, cut down by a new kind of death which it could not understand, which it denied, denied, denied, because some lizard instinct deep within told it that this was its last and only possible defense against a truth in which was written cataclysm, the end of all it had known. In Mask of the Red Death, though, this end has already arrived. It arrived a long time ago. There are just shades now, dim approximations of things that might have called themselves Important once, remains that do not know that they are nothing more than such, do not see that they are slowly disappearing back into the primordial clay, do not see their stiffness and their atrophy, do not see their doom, do not see because they do not know, do not know why they act, do not know what they do, do not know that they do at all, senseless as they are. They have forgotten everything, except the meaning of the death’s head, except their fear of it – a fear which still persists even now, long after the figure on horseback has come and gone.