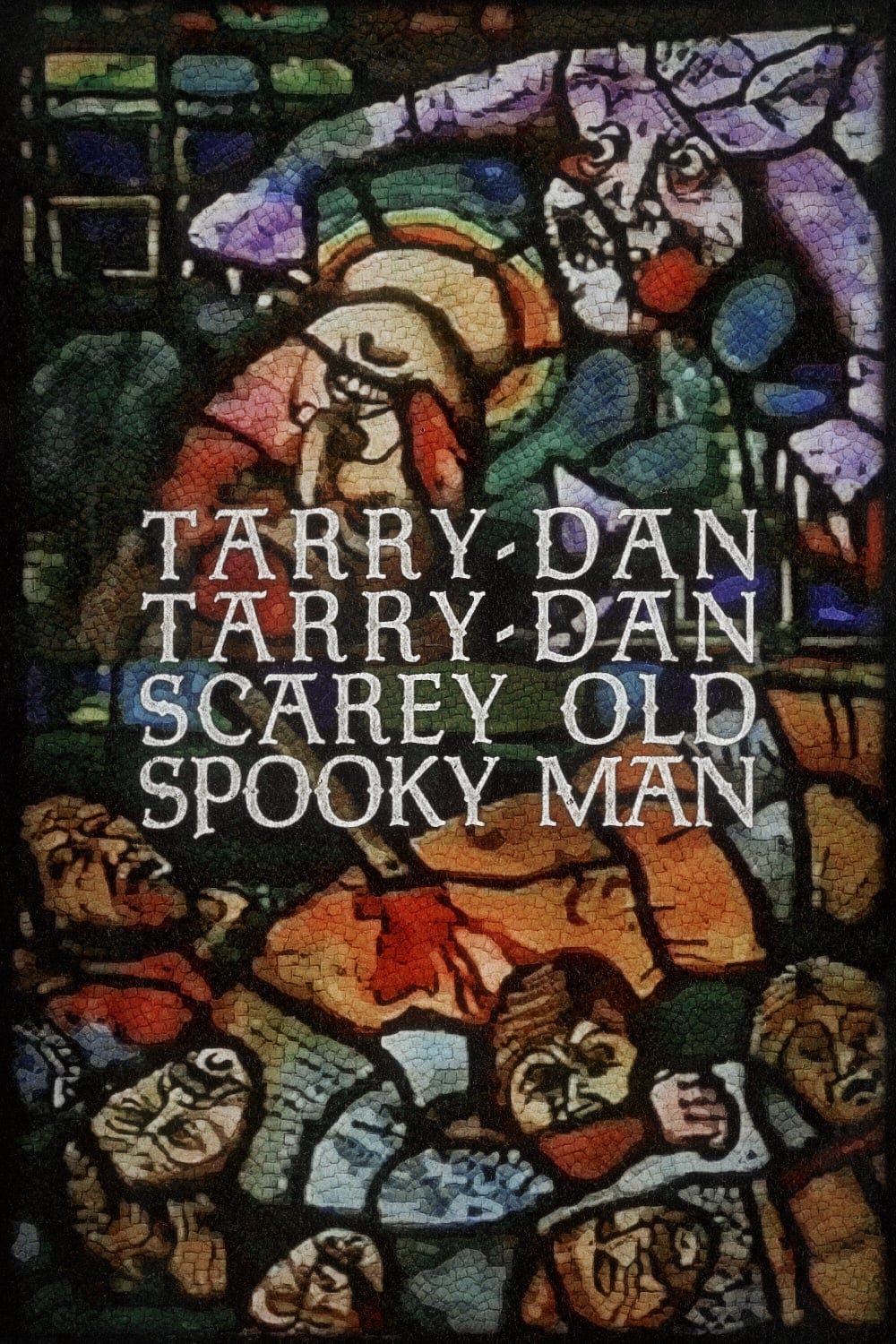

Minor Horror #2: Tarry-Dan Tarry-Dan Scarey Old Spooky Man

This is the second in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post.

Tarry-Dan Tarry-Dan Scarey Old Spooky Man (John Reardon, 1978)

It’s nice when a story has this much fondness for its little gang of delinquent innocents. The writer here is Peter McDougall, who’s mostly known for his grounded, character-driven dramas of Scottish life; folk horror, and Celtic folk horror, for that matter, is not his usual domain, and it shows in where its emphasis lies – not in what is happening to its protagonist, but in the effect it has on him, and those around him. There’s the dreams, yes, the unshakeable feelings, the gleam of the shining axe, yes, yes, yes, there is terror here, there is old, dark mystery, but before all that there’s just the four of them, on the cusp of sixteen and already smoking, drinking, pretending they’re tough, going nowhere faster than they realize. There’s not much time to get to know them, but you still feel like you do: there’s the leader, our protagonist – the world’s already started giving up on him, and he seems to have decided to return the favor; there’s his best mate – everyone says he’s got a good head on his shoulders, that he should know better than to hang around with this crowd, but of course that’s the secret, he’s here because he’s smart enough to know that real friendship is hard to come by, and with “this crowd” he’s found it; then there’s the other two, more in the background, less fleshed out, but there’s enough to fill in the gaps – one looking, as best he can, for a better life than his fisherman father, the other willing to speak up when others won’t, to pull back when he senses real trouble, who will be the first to admit he’s scared, and thereby give the others permission. They don’t quite feel like real people, but they feel like something like it, they have the right texture, you believe they’re derived from somewhere real, distilled from something true. They skip school, hang out in an old shed they call “the shed”, walk home alone at night on quiet streets. We never see their parents, any of them; they might as well not exist, except in the sense of a force which has sent them careening away, out, into the world, some time indeterminate ago.

Cornwall is the setting, and it’s distinctly unglamorous here, as perhaps it always is, a grey, stony city perched above a cold sea, very old, very weary, full of resigned things. The leader finds his name carved into the rock, deep inside a cave – the date is 1794, but “no, no,” says the history teacher, “that’s much too recent”. Something happened here a long time ago, a time that’s distant in a way that’s hard for him to imagine, for anyone to imagine. Cornwall is built on the ruins of it, this something which he dimly senses in his dreams – “squatting”, actually, like a beast over its kill. The old tramp wanders around with an old dog and a great burden etched into his face. The children have a mocking chant for him – the chant says he snatches children up, feeds on them. A strange form of mockery; they don’t seem to realize the role they write for themselves. Such is the privilege of childhood. “My dad was singing that when he was our age!” “Come on, he can’t be that old!” But of course the truth is he’s much older, much, much older; we don’t know the why yet, or the how, but we know this, we can tell, we can tell because it’s written all over his face. You would have to be blind not to see it. He looks at the leader, the leader looks back through a clouded window; he hates him, which is to say he fears him and doesn’t know why – he mistakes him for the world he must escape, when really he’s the truth within himself. At the church, his birthday comes, he passes out of childhood forever. He sees the glass which tells the tale, his tale; the church is abandoned – he has to break in through a boarded-up window. How much longer will it be here? How much longer until the story is forgotten, wiped away? The old tramp, fading away: “I hope you will be the last…” At the end, standing on the lonely ridge, it seems likely this is his hope, too. What would be the purpose? History is long, dark, deep, greater than a man can fathom. Most of it was already washed away a thousand years ago, two, three. One could continue like this forever, or one could let the burden go, let the weary spirits find their rest. But I can’t help but wonder, what will happen to his friends?