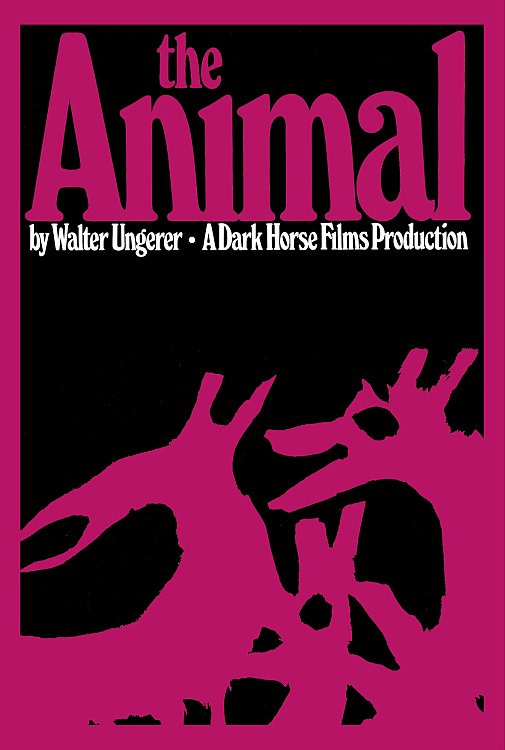

Minor Horror #02-11: The Animal

This is the eleventh in a series of fifteen pieces on “minor” horror films that I’m going to be publishing here throughout October. For more information, please see this post from last year, when I first did this.

The Animal (Walter Ungerer, 1976)

The Animal is a film which we call a horror film because we lack a more precise name for what something like it is. I mean, what other options are there? A fable? A mystic allegory? It almost could be a fantasy, in a very old-fashioned sense of the word (everything about this movie is strangely old-fashioned, untimely – “This whole place stinks of ancestors,” one character says, early on), but nothing fantastical really happens, at least not that you could pin down as such. Mostly ordinary things happen, mostly in daylight, all in calm and beautiful surroundings, in the snowy hills and ridges around Montpelier, Vermont1 – and all, all suffused with quiet, dusky dread. So we call it a horror film, and I suppose it must be. But it is far stranger than we are generally allowed to imagine a horror film can be, cut from such very different cloth.

Trying to describe what The Animal is “about” is both very simple and rather complicated. Let me reproduce the synopsis which first caught my eye, stumbling across the film on a torrent site several years ago:

A man meets a woman at a deserted railroad station somewhere in northern New England. It is the middle of winter; snow is falling. The two drive to a remote farmhouse. Two strange children, who never speak, appear at the window; an old woman calls them away. First isolation, then alienation, overcome the couple. The woman has a dream, then disappears. Nothing is explained. Only footprints remain in the snow that covers the supernatural landscape. The Animal is a film about unutterable loss, fate and the unknowable.

What would you make of a synopsis like this? It seems to raise more questions than it answers. How can an old woman calling away some children be an important enough event in a feature film that it warrants mention in the capsule summary? What about this New England landscape could be “supernatural?” I didn’t watch the film right away, not for the aforementioned several years, in fact, but I made a note of it, put it on the ever-lengthening watchlist, and the sheer oddness of this brief paragraph meant the thing kept resurfacing in my memory every few months, a puzzle I just couldn’t solve. Having now seen it, I can say that I’m skeptical there’s anything “supernatural” about the film’s landscape. That seems more like an attempt to avoid thinking about how strange the world really is, how full of secrets. On the other hand, I would agree that yes, the old woman’s call is important enough to warrant mention, although I find it hard to quite explain why, except, perhaps, by saying that in a film with as few characters as this one, every appearance of a new face seems important, especially appearing where the old woman does, outside this farmhouse, which does seem very remote, at the end of a long gravel track, and which is surrounded by drifts of soft, heavy snow, such that it’s hard to imagine anyone finding themselves there without a very definite purpose. We understand what the couple are doing there, they’ve come for the week, or the weekend, or something like that, get out of “the city” (they seem like people who live in a city, usually), do some cross-country skiing, probably try to resolve some simmering relationship problems. We can imagine, too, how the kids could have gotten out there, remote as it is; there must be other farmhouses somewhere around, and kids love to roam, especially kids living in places as rural as this, where there’s nothing better to do (and, indeed, what could be better to do, as a child, than to spend all day exploring in the woods, that vast and secret kingdom?) – but the old woman wouldn’t just have been “roaming,” so why was she right there, out in the yard? Where did she come from? How? And, again, why? And that call – what a strange, trilling, backwoods call, almost like a bird, but more formal somehow, almost ritualistic. Strange things have already been happening, strange footprints in the snow, animal tracks that cross the trails and go off through the thick of the woodland towards nowhere. It is strange, also, that the children have been there at all, have been there more than once, it is strange that they do not seem shy, or uncomprehending, yet refuse to speak to the woman (it is only the woman who tries to speak to them; it is uncertain if the man ever sees them at all, if they would even allow themselves to be seen by him). But it is only after this call, after the children heed it and run away, leaving the couple to themselves, alone with themselves, themselves and the woods, that these strangeness become serious, become mysteries with consequences, with stakes attached.

The simplest reason why The Animal is so unlike most “horror films,” even most I admire, is that Walter Ungerer (who I was sad to learn passed away last year, at the age of 88) was not a “horror filmmaker” – he was an artist who made films, “art films,” if you must, who was involved in the underground film scene in New York in the ‘60s, and who ended up in Vermont in the ’70s because Columbia kicked him out before he could finish his PhD because he was opposed to the mass torture and slaughter of the Vietnamese (no comment), and Vermont was where he could find a teaching gig. Most of his films could not be construed as “horror films.” The Animal can be only incidentally. First and foremost, it is a poetic film, a film which tries to tell us something true about the place in which it is set, and the things which might be found there, and the events which might occur – this is the type of film which Ungerer set out to make, and it is what he made. Fairly early on, the man reads aloud, to the woman, a story about an eccentric preacher who identifies a thief in the crowd which has gathered to hear his sermon by raising up a stone, and saying he will throw it, and saying it will strike the thief. A man in the crowd flinches, and in so doing reveals himself. But what if no one had flinched? What if they had all stood silent, even the thief, smiling placidly, waiting for the stone to be cast? This, perhaps, is the question which The Animal explores.

Thank you to the poet and Montpelier native Noam Hessler for the location ID here, as well as a bit of background info on Ungerer. Check out their very good debut collection Officeparks for more Authentic Vermont Poetics.